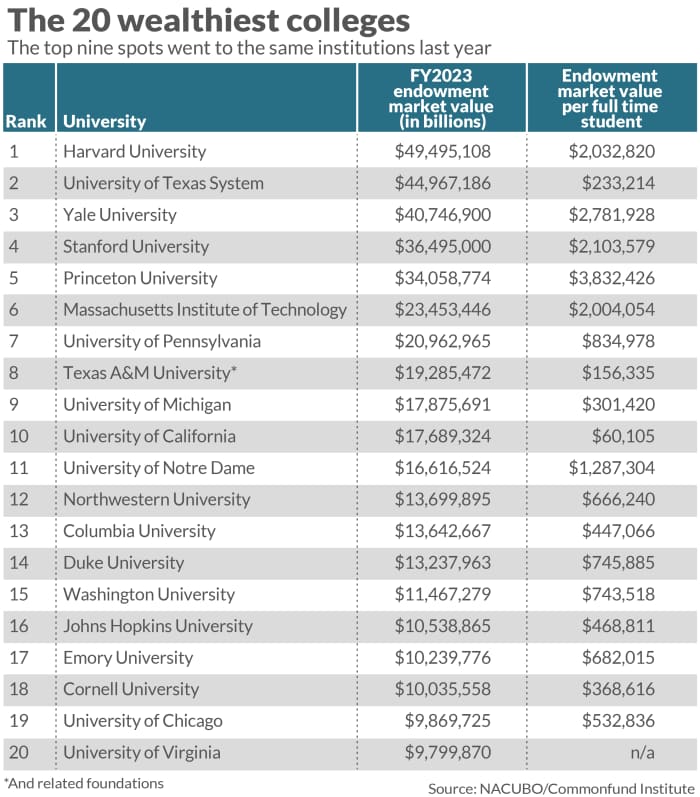

Harvard University’s endowment grew to more than $ 49.5 billion last year, making it once again the nation’s wealthiest college.

The University of Texas System wasn’t far behind with an endowment value of nearly $ 45 billion, while Yale University remained the third-richest school even as its endowment market value dropped slightly from last year.

The ranking of the nation’s largest college endowments is the result of a study of the financial assets of nearly 700 academic institutions, published Thursday by the National Association of College and University Business Officers and the Commonfund Institute.

Some institutions, like the University of California system, saw their fortunes swing over the last year. UC’s market value jumped 14.7% to nearly $ 17.7 billion, allowing the system to have the 10th-largest endowment and bumping the University of Notre Dame out of the No. 10 spot. The top nine university endowments by market value were unchanged from 2022. The average college endowment saw a 7.7% return in the last fiscal year ending June 30, 2023, according to the report.

The study showcased the significant wealth that some colleges have at their disposal. Harvard’s endowment, for example, is worth more than the annual gross domestic product of countries like Jordan, Bolivia and Paraguay.

The findings come amid continued debate over whether wealthy, tax-advantaged universities should receive more scrutiny. Following clashes on campuses across the country over topics like diversity, equity and inclusion and the Israel-Hamas war, conservative lawmakers have looked to target the endowments of rich, name-brand schools. In the past, college-access organizations and others have also questioned whether schools with large endowments should be spending more on making college financially viable for a larger swath of students.

“Whether the criticism is coming from the left or the right, there’s not a lot of people to stand up and defend the leaders of Ivy League institutions, and I think that’s in part because they’re not using their endowments to serve most Americans,” said Charlie Eaton, author of “Bankers in the Ivory Tower, The Troubling Rise of Financiers in U.S. Higher Education.”

The bulk of the money that universities drew down from their endowments last year was spent on financial aid. Schools used nearly 48% of their distributions, on average, for that purpose, according to the report. But there is an opportunity to do more, according to critics like Jennifer Bird-Pollan, associate dean of academic affairs at the University of Kentucky’s J. David Rosenberg College of Law.

“Where’s the growth going? What does that mean for the university? Or do you just sort of pat yourself on the back and say we had another banner year for the endowment?” she said.

Private foundations are required to spend at least 5% of their assets on charitable functions each year. Universities had an average endowment-spending rate of 4.7% last year, according to the survey. At universities with endowments over $ 1 billion, the average rate was 4.5%.

‘We don’t ever ask, how much is enough?’

Universities counter that endowments aren’t just piggy banks, but are rather meant to shore up the long-term future of the college. Additionally, schools are limited in the ways they can spend their endowment money because donors flag it for specific uses, colleges say. And institutions do use them to fund operations; on average, schools use their endowments to pay for 11% of their annual operating budgets, the study found. Schools with larger endowments said they funded 17% or more of their budgets.

Still, to Bird-Pollan, the focus on endowments’ growth and value highlights how disconnected they can be from universities’ priorities overall.

“We don’t ever ask, how much is enough? We just say more is always better,” she said. “I think it’s worth asking if that’s really true. What did the donors have in mind when they gave this huge amount of money to the university? Did they have in mind that it was going to go to some hotshot investment bank and not really be used for the functioning of the university?”

Part of that growth mindset is a result of the influence that the broader financial world’s strategies have had on endowment management over the past several years, Bird-Pollan said. Indeed, between fiscal years 1988 and 2023, the share of endowment assets allocated to alternative investments, like private equity and venture capital, went from less than 10% to more than 50%, the study found.

Typically, larger endowments perform better than smaller endowments — but that wasn’t the case last year. Schools with endowments valued at less than $ 50 million saw a 9.8% return, compared with 2.8% for schools with endowments over $ 5 billion and a 5.9% return for schools with endowments valued between $ 1 and $ 5 billion, per the study.

That’s because smaller endowments were more exposed to public equities, which performed better than these alternatives last year, Commonfund Institute Chief Executive Mark Anson told reporters on a conference call.

Still, the ability of larger endowments to withstand the kind of risk associated with alternative investments will probably allow them to fare better in the long term, said Eaton, an associate professor of sociology at the University of California, Merced. Smaller endowments may not be able to afford to subject themselves to the kind of short-term volatility associated with these kinds of assets, he noted.

That some schools’ endowments can weather swings in their investment performance indicates how disconnected the funds may be from some universities, Eaton said.

“When you’re endowment grows to be $ 50 billion a year, and it’s so large that it doesn’t really matter for the extent to which you can subsidize your university operations if you have a bad year, that’s kind of a sign that the old logic about endowments doesn’t really hold,” he said. That “old logic” is the idea that the endowment is there to ensure that each generation of students receive the same educational experience as their predecessors.

It’s not just the economic environment that can impact university endowments; the political environment may play a role, too. The survey indicated that culture-war politics may be having an influence on the approach of colleges’ investment managers.

About 35% of the universities featured in the study said they use some kind of responsible investing strategy, including ESG. That figure represents a “leveling off” after seeing growth in previous years, said George Suttles, executive director of the Commonfund Institute.

The “fraught” political climate may have caused some schools that were considering a responsible investing strategy to take pause, Suttles said.

For the third year in a row, the survey asked colleges about the share of gifts to their endowments that were tagged for diversity, equity and inclusion, or DEI. About two-thirds of schools said they received DEI-related gifts, a level similar to previous years. Overall, about 6.4% of gifts to colleges in fiscal year 2023 had a DEI purpose, according to the study.

But that may change. The period the survey covers ended just as the Supreme Court issued an opinion banning affirmative action at colleges — a ruling that some experts have said could impact gifts and financial aid. In addition, the reporting period ended before the recent donor backlash toward colleges’ approach to diversity, antisemitism and other issues.

NACUBO Chief Executive Kara Freeman called the issue of DEI “extremely important, as it gets to core mission,”

“Institutions of higher education must reflect both the students they serve and the communities that surround them,” she said in an email. “At the end of the day, our endowments must help leverage and enhance our teaching, research and service capabilities.”