Long-dated Treasury yields reached their highest closing levels in well over a decade on Thursday, undermining investors’ confidence, injecting uncertainty in the stock market, and threatening the U.S. housing market.

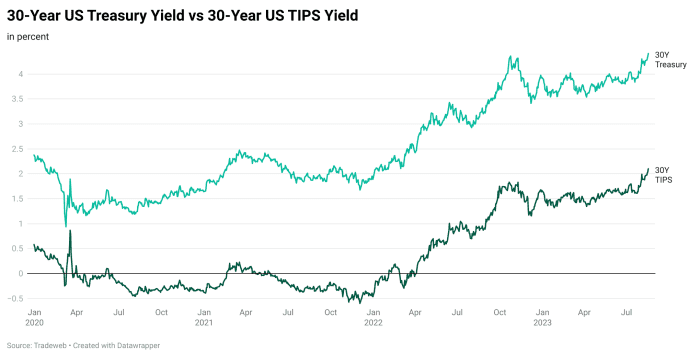

The benchmark 10-year yield BX:TMUBMUSD10Y finished at its highest close since Nov. 7, 2007, at 4.307%, while the 30-year rate BX:TMUBMUSD30Y ended at 4.411% or its highest since April 28, 2011. The 30-year rate has jumped 87.3 basis points since April, while its 10-year counterpart has soared more than a full percentage point since then.

Conventional wisdom is that rising long-term yields tend to reflect a combination of greater optimism about U.S. economic strength, the prospects for future inflation, and investors’ demands to be compensated for the risk of those future price gains. This time around, inflation expectations are still elevated, but easing, and there’s a bit more going on.

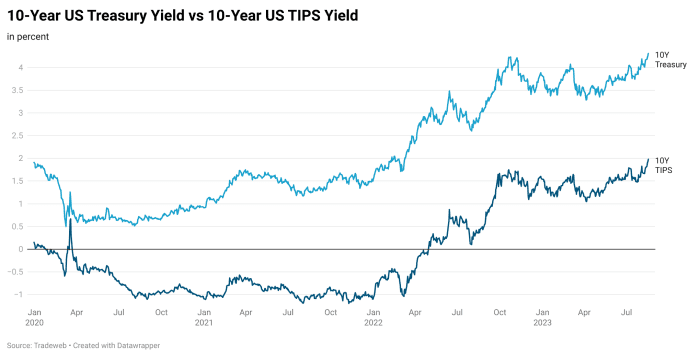

Nicholas Colas, co-founder of DataTrek Research, said “the root cause” behind the U.S. government-debt market’s moves is higher real yields and that the 10-year Treasury yield could “easily reach” 4.5%-5%. Real yields reflect the difference between the expected levels of inflation and nominal Treasury rates.

Read: How higher-for-longer rates are playing out as 10-year yield hits 15-year high

“Higher inflation expectations are not the reason 10-year yields are breaking out; real rates are the problem,” Colas said in a note on Thursday. “The breakout in real rates is a good reminder that we are far from levels consistent with historical tops for this component of nominal interest rates.”

The upshot is that even if inflation expectations do decline to 2%, nominal rates could run between 4%–4.7% over the next six to 12 months, he said.

In a nutshell, 10- and 30-year Treasury yields are a reflection of where the bond market sees the U.S. economy heading over the long term. They’re now capturing the likelihood of a higher-for-longer fed-funds rate, plus higher real yields, while unwinding the risk of an imminent recession, strategists said.

Meanwhile, 10- and 30-year real yields — as measured by rates on Treasury inflation-protected securities, or TIPS — provide a look at how the underlying economy is performing after subtracting inflation. Higher real yields also indicate that the inflation-adjusted cost of borrowing is going up. As of 3 p.m. Eastern time on Thursday, the 10-year TIPS yield was at 1.979% and the 30-year TIPS yield was at 2.102%, according to Tradeweb. Those are respectively the highest levels since mid-March 2009 and mid-February of 2011.

Source: Tradeweb

Source: Tradeweb

Stock and bond markets reacted strongly to the minutes from the Federal Reserve’s July 25-26 meeting on Wednesday because of the signal being provided about policy makers’ views on long-run real interest rates, according to Colas.

The minutes suggest the policy-setting Federal Open Market Committee “wants to see higher real yields across all maturities to slow growth and contain inflation,” he said. “All this will contribute to near-term equity market uncertainty, dampening investor confidence/valuations.”

Real long-term rates of 2%-3%, or levels seen in 2006-2007, could also reduce consumption and investment by increasing the cost of consumer debt and corporate cost of capital.

The Treasury market appears to be in the early stages of a “higher-for-longer” environment for U.S. rates, one that might be jarring for investors long accustomed to easy borrowing. Both the 10-year Treasury and 10-year TIPS yields are now in territories which have historically been regarded as normal for the U.S. economy.

“One could say that Treasury yields are simply returning to their natural equilibrium,” said Christoph Schon, the U.K.-based senior principal of applied research at Qontigo, a financial analytics and index provider. A nominal 10-year yield of 4.3% “seems appropriate” when considering current inflation expectations and where Treasury rates have historically traded.

One important area of the U.S. economy may be about to take a hit: the housing market. Economists said mortgage rates could climb to 8% if the economy continues to show signs of strength and the Fed its benchmark interest-rate target again. Last month, policy makers raised borrowing costs to between 5.25%-5.5%, the highest in 22 years.

On Thursday, a day after the Fed’s July minutes opened the door to more rate hikes, Treasury yields finished mix. Meanwhile, all three major U.S. stock indexes DJIA SPX COMP ended lower, with Dow industrials off by 290.91 points .