After a difficult two years, inflation appears to be easing its grip on the American economy. Overall prices increased by a mere 0.1% month-on-month in November, according to data published on December 13th, making for that rarest of recent occurrences: a downside surprise. More promising was a breakdown of the data showing that core inflation, which strips out volatile food and energy costs, had decelerated for a second consecutive month. Some of the underlying pressures which have pushed up prices are receding.

Investors and analysts, scarred by America’s relentless run of inflation, have learned to restrain their hopes after a single month of rosy data. Year-on-year rates of inflation remain high at 7.1% for headline inflation, and 6% excluding food and energy costs. But the disinflation in November follows a similarly cheerful batch for October. Optimism is on the rise, albeit still mostly of the cautious rather than the unbridled kind. The s&p 500 index of leading American firms climbed by roughly 2% after the price data, building on a steady rally since mid-October.

The relief stems not just from the view that America’s inflation fever is breaking. There is also hope that the Federal Reserve will become less hawkish. It has already jacked up interest rates from a floor of 0% in March to nearly 4% today, the sharpest bout of monetary tightening in America since the early 1980s. On December 14th it is expected to raise rates by a further half-point, a hefty increase but a step down from the three-quarter-point increments that it has opted for in recent months. Will the Fed now halt rate rises before too long? Prior to the latest inflation data, most investors reckoned rates would pass 5% by the middle of 2023. Bond pricing now points to a peak of less than 5%.

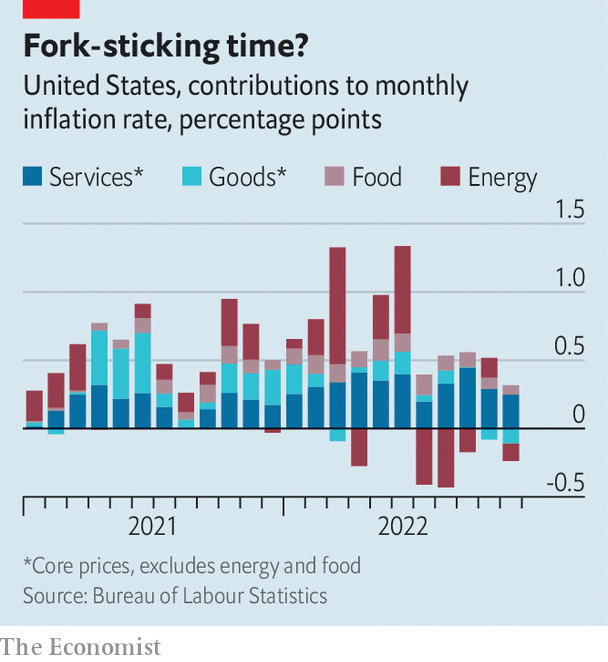

The biggest drag on headline inflation in November was a decline in energy costs. But the most encouraging development was the breadth of deflation. Many of the consumer goods that were in short supply during the covid-19 pandemic are now readily available. Prices for cars, children’s clothing, furniture, televisions and toys all declined. Trends also turned more favourable for services, which have taken over from goods as the principal inflation driver. Looking ahead, there is reason to think that disinflationary forces will gather steam. Market-based measures of housing prices have fallen sharply over the past half year but will only show up in official inflation data next year. Though wage growth remains ultra-fast, it too may be gently falling as companies pare back hiring.

Indeed, concern may soon start to shift from high inflation to low growth. The nature of monetary policy is that it always operates with a lag. It takes months for rate changes to filter through into investment and spending decisions—much of the tightening implemented so far will only hit the economy next year. The median expectation of professional forecasters is that America will experience a recession in the first half of 2023. Capital Economics, a research firm, declared: “Stick a fork in it, inflation is done”. That is premature, but for once the news is promising. ?