SHANGHAI, CHINA – JULY 06: A security man with protective mask stands on a pedestrian bridge which displays the numbers for the Shanghai Shenzhen stock indexes on July 06, 2022 in Shanghai, China. (Photo by Hugo Hu/Getty Images)

It’s time for emerging Asian markets to reap the rewards after years of building up foreign-exchange reserves, as they become the latest destination for risk investors.

While no market has come through 2022 unscathed, countries from Indonesia to South Korea and the Philippines are reaping the rewards of a quarter-century preparing for a repeat of the turmoil that set off the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s. Even as the dollar rallied, emerging Asia’s currencies are mostly faring better than traditional havens like the yen and the euro. The region’s bonds are standing out as a rare bright spot in a year that sent global debt into its first bear market for a generation.

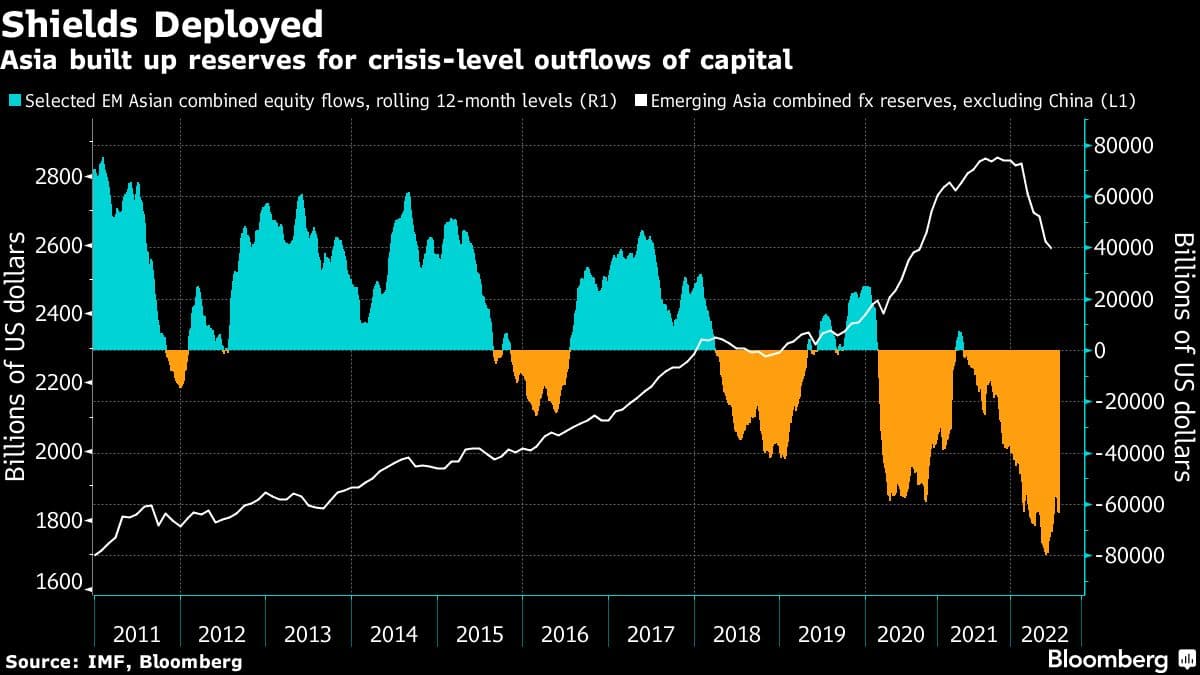

Asia is benefiting from both good management and good luck. Inflation is weaker than for much of the globe, and local policy makers not only built up record foreign-exchange reserves but also have been moderate in their deployment. Fiscal prudence and calm crisis management have been the norm, and while those reserves have shrunk at the fastest pace on record, they are still higher than they were at the end of the last decade.

“Emerging Asia leads in the race to keep inflation low,” said Swiss Re Chief Economist Jerome Haegeli. “Countries that can avoid stagflation-like conditions — and we currently think most of Asia will — could gain competitiveness.”

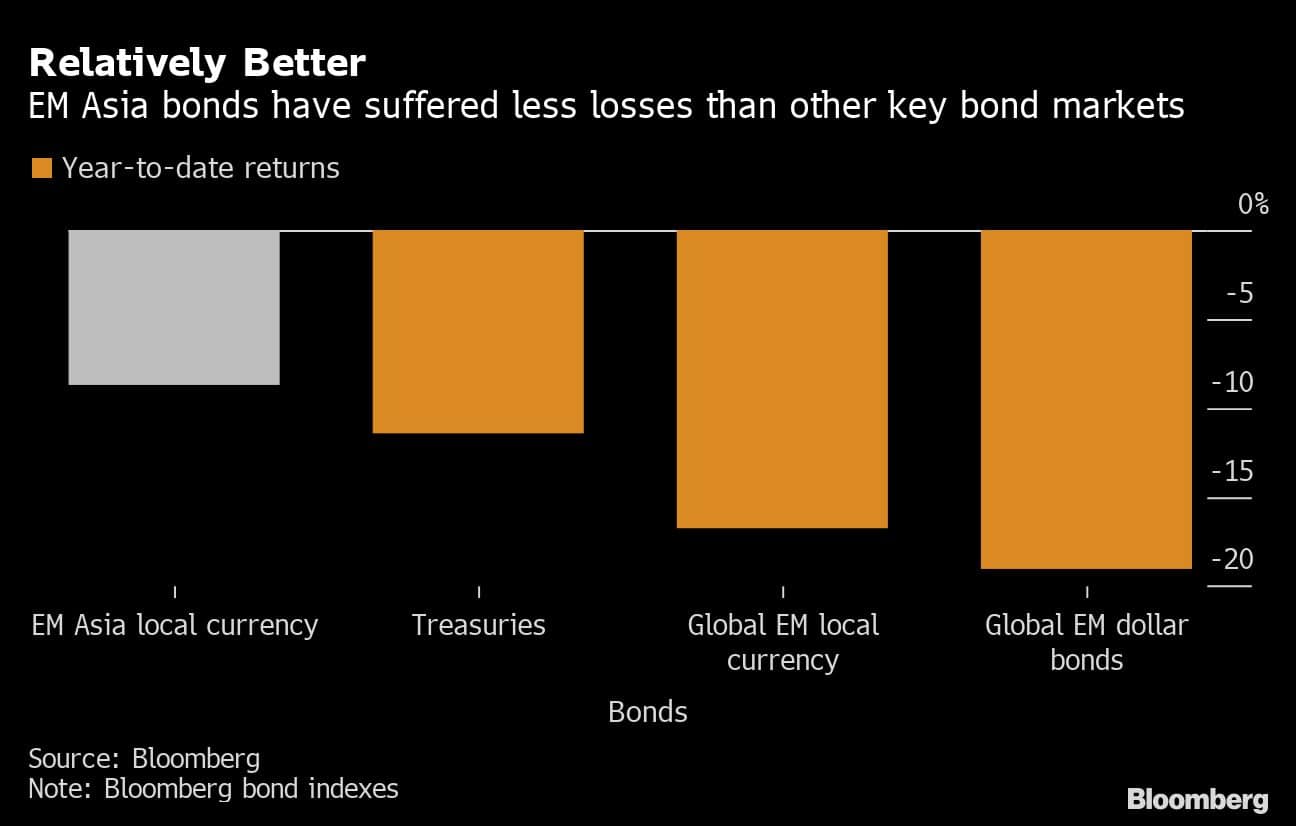

Year-to-date performance may have given some vindication to bullish emerging Asia investors. A Bloomberg index of emerging Asia bonds registered total losses of around 9% this year, comparatively better than a gauge of US Treasuries which saw losses of 11%, or a global emerging-markets barometer which dropped over 16%.

That’s led global investors in a pivot back into Asia. India and Indonesia recorded net foreign bond inflows in August, their first addition in at least six months, while global funds poured into Thai debt for the first time since May. Foreign bond positioning has still yet to recover to pre-Covid levels in most Asian economies, suggesting lower odds of capital outflow even if macro conditions tighten again, says Galvin Chia, a strategist at Natwest Markets in Singapore.

Swiss Re’s Haegeli points to relatively lower factory gate prices in Asia as a key indicator of a better outlook for the region. That’s partly driven by the region’s good fortune in avoiding the worst of the commodity price shocks, because East Asia is less dependent on energy from Russia or wheat from Ukraine.

The foreign-exchange stockpiles Asian economies built up have helped cushion the impact of this year’s market turmoil, which has spurred the largest equity outflows for at least a decade. There has been some alarm as the reserves were drawn down, but they are still above where they stood at the end of 2019. Emerging Asia’s combined holdings are at $ 2.6 trillion, after peaking above $ 2.8 trillion in October.

“Over the last year external buffers that were built up have been heavily depleted –- public and private debt has increased substantially, fiscal spending has increased, higher commodity imports are eating into current account surpluses, and real interest rates are negative, implying less of a buffer against capital outflows,” said Alexander Wolf, head of Asia investment strategy at JPMorgan Private Bank in Singapore.

Southeast Asia in particular is showing some macroeconomic resilience, with manufacturing PMIs signaling expansion across those nations, a contrast to the contractions for South Korea and Taiwan. The troubles afflicting north Asia — especially the behemoths of China and Japan — could be the region’s Achilles’ heel. JPMorgan’s metrics for judging countries’ vulnerabilities, based on current account levels, foreign-exchange reserves and yield buffers, show Thailand and Japan are among the weakest, with China, South Korea and India in the next-weakest tier.

Seven out of 30 major economies were found to be less vulnerable to hard landings, and those in Asia include Indonesia, Malaysia, Taiwan, the Philippines and India, write Nomura analysts including Rob Subbaraman in a Sept. 13 note.

To be sure, China’s pursuance of a Covid-Zero strategy has weighed on the domestic outlook, as well as on demand for exports from the region. And part of this weakness has been seen in the depreciating yuan, which crossed the key psychological level of 7 against the dollar last week. But China has pursued fiscal and monetary easing to soften any potential hard landing in the economy, with recent August industrial production, retail sales and fixed-asset investment data showing nascent signs of a recovery.

“Asia still has the buffers to weather the storm.” said Jin Yang Lee, an investment manager for sovereign debt at abrdn Plc in Singapore. He sees opportunities in Malaysian, Indian and Chinese debt, along with pockets of the South Korean market. “In general Asia has been much more prudent in their policy settings vis-a-vis structural changes in their economies.”