The white house used to dread monthly inflation reports, each one worse than the previous, each another blow to President Joe Biden’s popularity. Now the reports are less fearsome. In the latest release on September 13th, the consumer-price index for August rose by 8.3% year on year. But in month-on-month terms, prices rose just 0.1%. These days Republican strategists are advising their party to tone down criticism of the president’s record on inflation, seeing it as less of a winning argument.

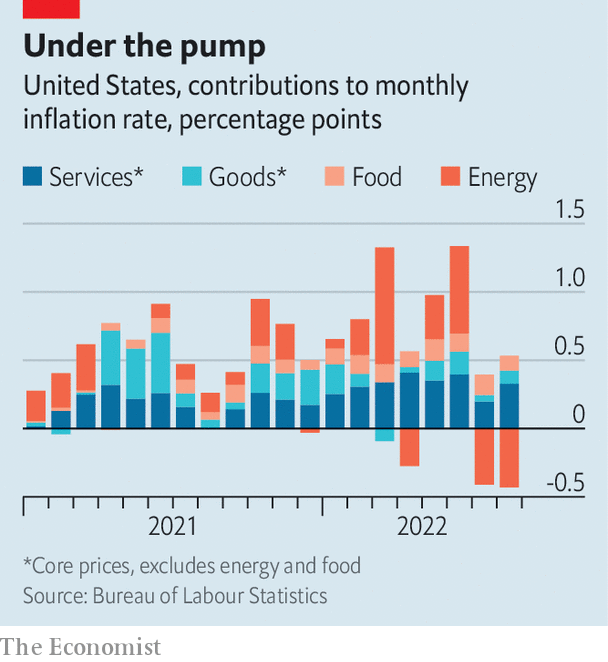

But for economists the newfound optimism is a harder sell. The less fearsome data mainly reflects a steep fall in oil markets. The price of crude is down a quarter from its peak in early June. Looking at a breakdown of the August price data, energy lowered the month-on-month inflation rate by nearly half a percentage point. It was the other components—food, goods and, especially, services such as rent—that pushed up prices (see chart).

Stripping out volatile energy and food prices yields a core inflation rate of 0.6% month-on-month in August, which works out at an annualised rate of 7.4%—well above the Federal Reserve’s target of 2%. Investors believe the Fed will opt for its third consecutive three-quarter-point interest-rate increase when it meets later this month, making for the most aggressive pace of tightening in four decades.

One critical factor in explaining the persistence of high core inflation is tightness in the labour market. With roughly two jobs available per unemployed person in America, workers have strong bargaining power, which is reflected in hefty wage gains. A tracker published by the Fed’s Atlanta branch shows that in August wages rose at an annualised pace of nearly 7%. The grim conclusion for many economists is that America may require a marked increase in unemployment in order to temper wage pressures and, ultimately, inflation.

The median projection of members of the Fed’s rate-setting committee is that the unemployment rate will only need to tick up slightly to 4.1% in 2024, from the current level of 3.7%. But a recent paper by Laurence Ball of Johns Hopkins University and Daniel Leigh and Prachi Mishra of the imf argues that a 4.1% level of unemployment would be consistent with core inflation of between 2.7% and 8.8% in 2024. In other words, only in the rosiest scenarios does it look like America can escape from the inflationary mire without many people losing their jobs.

Nevertheless, the divergence between core and headline inflation poses an intriguing question. As far as consumers are concerned, there is no such distinction. All prices matter, and indeed prices at the petrol pump do more to capture the attention of Americans than prices anywhere else. Surveys of consumers show that their expectations for future inflation have come down sharply since June, undoubtedly thanks to the decline in oil prices.

As Mr Ball and his co-authors argue, a failure to account for the pass-through from surging energy prices into core inflation was one reason why economists were wrong-footed about inflationary pressure over the past year. The hope now is that the plunge in energy prices can continue, and that the pass-through into weaker core inflation will again wrong-foot many economists. ?