It was July of 1982. Ronald Reagan was president. The theme song “Eye of the Tiger” from Rocky III topped the music charts. And baseball star Cal Ripken began his Iron-Man streak of starting 2,216 straight games.

It was also the last time U.S. inflation was as high as it is now.

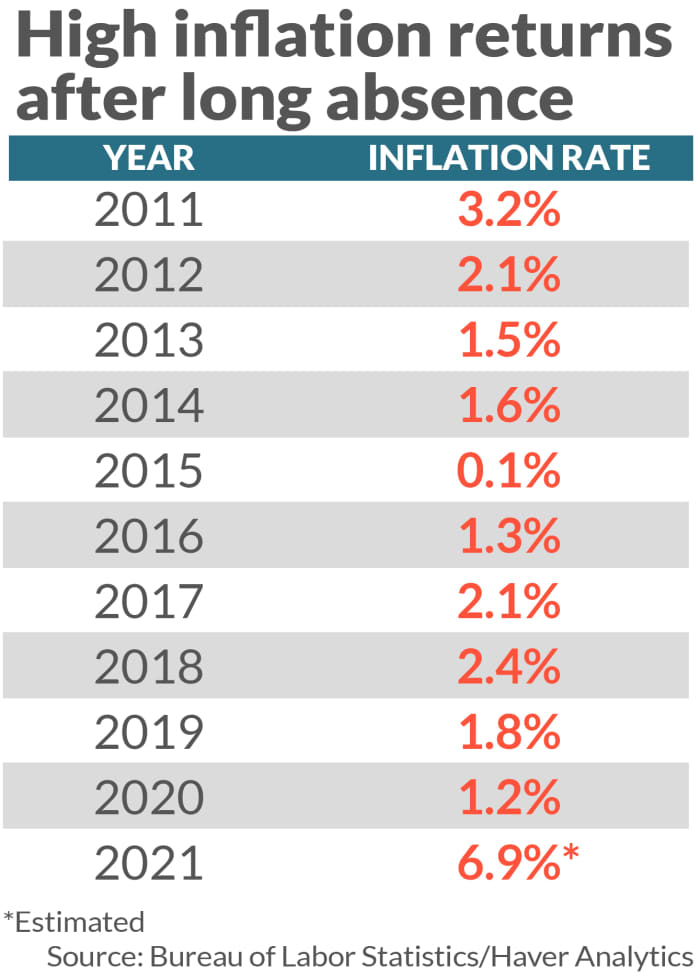

The yearly rate of U.S. inflation — measured by the consumer price index — climbed to 6.8% as of November to mark the sharpest increase in prices in 39 years.

See: Sticky inflation, bigger paychecks, fading stimulus – how the U.S. economy is shaping up for 2022

A lot has changed in the past 40 years, of course, and Wall Street DJIA, +0.17% economists say comparing the two episodes of high inflation is like night and day.

Prices in the 1970s and early 1980s rose a lot higher, for instance, and the structure of the economy was quite different. Labor unions were more powerful, businesses faced less global competition and the U.S. economy was far more dependent on oil.

All of those things contributed to higher and higher prices, especially after the end of the Bretton Woods currency exchange system and the OPEC oil embargo unleashed a period of runaway inflation.

The current inflation spiral, on the other hand, erupted suddenly after a long period of low and relatively stable prices. Inflation rose an average of less than 2% a year in the decade before the Covid outbreak.

Most of the recent inflation also has been spawned by what are likely to be temporary shortages of business supplies and labor as lockdowns to combat the spread of Covid disrupted supply chains.

These shortages grew quite acute after the economy fully reopened in early 2021 and could persist well into 2022 before receding.

Yet both episodes of high inflation do share a few things in common.

For one thing, easy-money policies.

The Federal Reserve was particularly lax in the 1970s during a period of great economic volatility. As a result, the yearly rate of inflation peaked at 14.8% in 1980 and hit the second highest level on record.

This time around, the Fed slashed short-term interest rates to near zero and pumped trillions of dollars into the economy through a still-controversial tool known as quantitive easing.

Another similarity: High government spending.

The U.S. ramped up spending in the late 1960s and it went on for the next two decades as high inflation fed back into even more government spending.

In the past year and half, meanwhile, Washington injected some $ 5 trillion into the economy in the form of stimulus payments to families and businesses to contain the damage caused by the COVID pandemic.

The flood of stimulus money easily surpassed the last full year of government spending before the crisis. The U.S. spent $ 4.4 trillion in fiscal 2019.

The next year or two could look quite different, though.

Surging prices have forced the Fed to speed up plans to end its massive stimulus strategy. The central bank could even begin raising interest rates by mid-year.

The Biden administration, under public pressure, is also seeking ways to ease the runup in prices.

What’s more, government spending is likely to fall sharply as the stimulus fades and the White House runs into more roadblocks on its big-spending plans.

The president’s $ 2 trillion Build Back Better plan has stalled in Washington and Republicans appear poised to capture control of part or all of Congress in the 2022 elections, polls show. A Republican-led Congress would likely block any major spending bills.

In the private sector, companies are slowly figuring out how to cope with the supply bottlenecks and to boost production through automation or other means. The supply shocks should ease considerably in 2022, though it’s less clear the labor shortage will clear up as quickly.

Still, many economists question whether inflation will return to pre-crisis levels of less than 2%. The longer the period of high inflation goes on, they say, the more likely some of it becomes embedded into the economy.

“If we go into next fall with inflation at 3%,” said Joel Naroff of Naroff Economic Advisors, “then the Fed’s 2% long-term inflation target is out the door.”