The 60/40 stock-bond portfolio, given up for dead in recent years, is outperforming almost all the sophisticated endowment portfolios at elite educational institutions.

Read: ‘We’re not in Kansas anymore’: Why the 60/40 portfolio might be dead, and what to do now

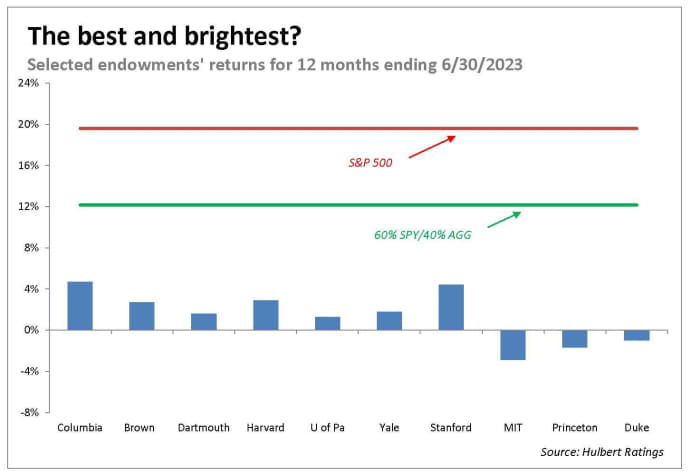

It’s not even close, according to results released this week by most colleges and universities for their fiscal years ending June 30. In contrast to a 12.2% return for a plain-vanilla 60/40 portfolio, Ivy League university endowments produced returns in the low single digits — if they made any money at all. This is illustrated in the chart below.

The longer-term view paints only a marginally better picture. I calculate that the median college and university endowment has lagged behind the 60/40 portfolio over the last 5-, 10- and 15-year periods by margins in the range of 2 to 4 annualized percentage points. The endowment returns are from the National Association of College and University Business Officers.

Opinion: Sell the S&P 500. Buy this instead.

How could these “best and brightest” institutions so significantly lag the public markets? One of the biggest reasons almost certainly is that college and university endowments have shifted away from the public stock and bond markets and invested heavily in alternative investments. They no doubt were seduced by the huge success of Yale’s endowment in the 1980s and 1990s under the famous direction of the late David Swensen.

Harvard’s endowment, for example, has just 11% invested in public equity and 6% in bonds, according to N.P. Narvekar, the CEO of Harvard Management Company, which manages the university’s endowment. Almost all other college and university endowments have a similarly low allocation to public markets and high allocation to alternative assets. This is why their latest fiscal-year returns are so closely clustered together.

The huge influx of new money into alternative assets killed the goose that lays the golden egg, according to William Bernstein of EfficientFrontier.com, the author of the 2010 book “The Four Pillars of Investing.”

“Swensen got to the alternatives banquet table first and loaded up on lobster tails and prime rib,” Bernstein wrote in an email, “and those who followed … got the tuna noodle casserole.”

To illustrate his point, Bernstein asks us to imagine that, 25 or so years ago, approximately $ 300 billion was invested in hedge funds, and they collectively went after approximately $ 30 billion of available “alpha.” He says that these numbers, while crude estimates, are order-of-magnitude accurate.

“That’s 10% of excess return, which covered the 2 and 20,” he said, referring to hedge-fund fees of 2% of assets under management and 20% of profits. “Now there’s $ 3 trillion chasing the same (or likely less) alpha [and] the excess [alpha] is only 1%.” That isn’t even enough to pay the hedge-fund fees, of course.

There’s some solace for the rest of us in these mediocre or worse endowment returns. We’ve not been missing out by not being given as much access as large institutions have to hedge funds and private-equity funds. We may even be far better off.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com.