The political climate in France has been running hot, with weeks of disruptive protests and strikes in reaction to a bump higher in the pension-collection age. Over an intense few days, Israel’s economy, including its major airport, was hobbled by a broad work stoppage that made frenemies of business owners and labor against a hardline government because of proposal giving greater power to its judiciary.

These are demonstrative examples, no doubt, featuring compelling images of roaring bonfires mere feet from occupied Parisian café tables and of major roads choked with angry crowds in populous Tel Aviv. Even the strike-reluctant U.K. has seen workers doggedly pursue collective bargaining for wage hikes to, they say, have a fighting chance against inflation. But behind dramatic footage not uncommon historically in Europe and other global capitals lurks a much larger truth, say historians and analysts.

Much of the world feels let down by democracy and by leadership power flexes that make the unpowerful feel even smaller, they say. Citizens are stung by higher food, housing and medical costs, they just watched another rescue of the banking sector, and they’re worried about how long Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could leave energy markets unstable.

Analysts say generalized discord percolates in the U.S. to a greater degree than the powerful on Wall Street SPX, +1.42% or in Washington might want to admit.

At a minimum, the U.S. is watching major allies and trade partners challenged from within in ways that stretch beyond traditional labor walkouts. Israeli-U.S. relations, for instance, grew strained in recent days when President Joe Biden chimed in on the volatile situation kneecapping Israeli leadership. The U.S., of course, is facing its own financial reckoning amid rising interest rates and stubborn inflation, particularly for housing costs and food. Student-debt relief has been held up in the courts, while gun control and social issues sharply divide the parties and voters.

“French protests aren’t new, but these protests are more intense and in some ways, resemble what is going on elsewhere, in the U.S. even, because social and economic pressures were bottled up during the pandemic and released over time,” said Gabriel Winant, an associate professor of history at the University of Chicago, whose specialty includes the social structures of inequality in modern American capitalism.

“A number of these actions can be linked to what many feel is the erosion of democratic government,” he told MarketWatch.

Read: Israel protests explained: Netanyahu’s judicial reform, and why thousands of workers are on strike

“ ‘A number of these actions can be linked to what many feel is the erosion of democratic government.’”

On Monday, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu postponed for at least a month — but vowed to then resume — an effort to change how Israel appoints judges to its Supreme Court.

The court is especially pivotal in Israel and could rule over future legislation from the right-wing Netanyahu’s coalition or eventually over Netanyahu’s own corruption trial. Netanyahu’s move to shape the court triggered a general strike, political division, including the firing of a key minister, and mass protests for what most consider to be the country’s most severe domestic crisis in years.

And second-termer French President Emanuel Macron, who dealt with “yellow-vest” labor strikes over taxes in his first administration, “has never been in as much trouble as in recent days,” wrote Michele Barbero for Foreign Policy magazine.

Macron’s decision on March 16 to force through a wildly unpopular pension reform bill, essentially pushing up the retirement age, without a final vote by the National Assembly and instead invoking a controversial article of the constitution to assure passage, “has infuriated opponents and sparked one of the most serious crises in the history of France’s Fifth Republic,” Barbero said.

‘A lid on populist energies’

The University of Chicago’s Winant said France is facing a class conflict as Macron, long-billed as a centrist, has wanted to “put the experts in charge and put a lid on populist energies. He’s a figure head of the French elite and the French professional upper middle class.”

And that, said the professor, is a notable distinction in his mind from Israel, where “it’s secular civil society as a whole versus Netanyahu’s deepening alliance with the religious right. You paradoxically had business and labor cosponsoring a general strike.”

An aerial view shows crowds protesting in Tel Aviv against the government’s controversial judicial overhaul bill, on March 25.

AFP via Getty Images

Notably, these actions in the news in recent weeks push beyond typical labor strife, although there are similarities — class differences and contemplating the reach of government among those traits.

Spain’s last economy-hobbling general strike was more than 10 years ago, against the labor reforms of the Mariano Rajoy government. But smaller actions have bubbled up. Last spring, a 20-day nationwide trucker’s strike called by several unions over high petrol prices snarled logistics for businesses and households. A similar strike lasted just a couple of days in November.

Earlier this year, the taxi drivers in Madrid walked, protesting the “Uberization” of the city with competing new-economy rideshare UBER, +2.66% drivers. Most recently, demonstrations numbering in the tens of thousands through Madrid’s main Gran Via street featured white-coated medical workers and public supporters over cuts to the healthcare system. Health-benefits protests have been building across the country.

And yet the main difference in Spain over France? The Spanish government is working closely with unions, which is keeping larger protests at bay. The left-wing leadership hasn’t adopted any policies that would trigger a major reaction by trade unions so far, said Antonio Barroso, deputy director of research at global political advisory firm Teneo, speaking to MarketWatch.

“A lot of people are striking in Europe because inflation is going up,” he said, “so you know, wages don’t keep up with inflation, and this creates actually a conundrum for policymakers because you don’t know for how long inflation is going to stay high.”

Indeed, across Europe, high inflation is linked partly to Russia’s year-plus invasion that has specifically hit continental Europe hard, driving up everything from energy NG00, -1.14% to food prices. Major central banks the world over, including the U.S. Federal Reserve, are raising interest rates, a boon for the investment class in many respects, but making it much harder on house hunters and other borrowers.

“ ‘A lot of people are striking in Europe because inflation is going up, so you know, wages don’t keep up with inflation, and this creates actually a conundrum for policymakers because you don’t know for how long inflation is going to stay high.’ ”

France, ironically, has the lowest inflation in the eurozone because the government spends so much to keep energy prices low, Barroso said.

“The main issue, the lightning rod, so to speak, is financial reform,” Barroso said.

Are disruptions to work and civic life effective?

France’s unions and protestors seem to believe that a sustained wave of disruption will force the government to withdraw the pension reform, but Macron has not given any indication that he will back down. He might be betting that public support for the protests will eventually wane as the government moves on to other, less-unpopular issues, analysts say. But protesters may be in it for the long haul. “The coming weeks will probably see a battle of wills” between the government and trade unions. That means disruptions, the Teneo analysts said in a note.

Do those disruptions tend to work, meaning produce results for those protesting, especially at the highly-visible scale of the past few weeks?

In Israel, for example, departing flights from the country’s main international airport were grounded, while large shopping-mall chains and universities shut their doors. Israel’s largest trade union called for its 800,000 members — spanning healthcare, transit, banking and other fields — to stop work.

“Social science suggests economic disruption by work stoppage is a powerful lever,” said Winant. “The risk to the populists’ cause at times, however, can be that political dysfunction can sometimes allow the super rich to set the agenda if they’re best positioned to rise about the chaos.”

Yet, as the U.S. began to recover from the coronavirus pandemic in 2021, there was a well-documented shift of worker power in the labor market. This shift in power was primarily fueled by a substantial macroeconomic policy response—particularly the American Rescue Plan Act—that led to a rapidly growing economy and very strong demand for workers, said a report from the Economic Policy Institute.

One of the most prominent forms of worker power starting in 2021 and 2022 was the use of strikes. When thousands of workers across the nation went on strike for fair pay and better working conditions in fall 2021, the media dubbed the month of October “Striketober.” Throughout 2021, strikes provided workers critical leverage to bargain over fair pay, safe working conditions and a share of the pandemic recovery, the report documents.

Read: ‘Our labor laws are designed to make joining a union as difficult as possible’: Fewer workers are unionized, even as pandemic shines light on poor working conditions

And: Apple accused of firing unionizing workers

Reaction to labor demands can come from surprising places. Just this week, mere hours after former Starbucks Corp. SBUX, +1.92% Chief Executive Howard Schultz was accused of union-busting in front of a congressional committee, the company said its investors have asked for a third-party assessment of the coffee chain’s commitment to worker rights.

“The truth is, that workers are losing purchasing power, so that explains why in several countries you have this movement to support higher wages sometimes channeled through negotiations between trade unions and employees. In some places they are successful, in others they are not,” said Teneo’s Barroso.

There is some risk, say observers, that worker issues and broader social issues are becoming muddled.

“There is a debate around the trade union movement, about having to better distinguish mobilizing against employers [through collective bargaining] from the type of mobilizations in France, which are directed against the Macron government, or in the U.K., were workers are in public-pay disputes with the Tory government,” said Eoghan Gilmartin, a Madrid-based writer on labor issues for mostly left-leaning publications.

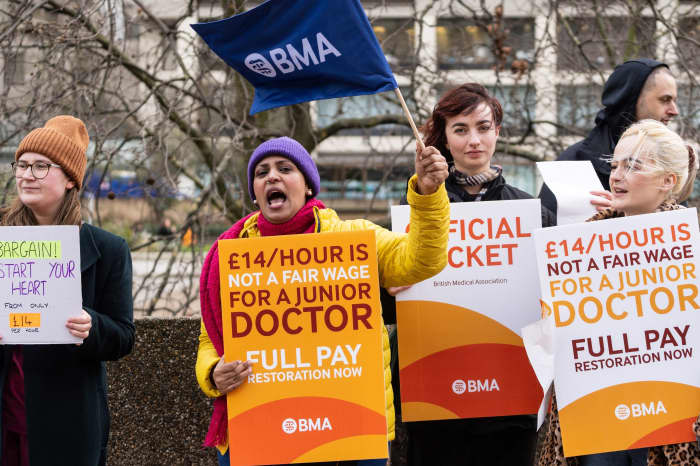

Demonstrators take part in a protest by junior doctors amid a dispute with the government over pay, outside of Saint Thomas Hospital, in London, on March 13.

AFP via Getty Images

‘A version of this here’

Back in the U.S., the University of Chicago’s Winant said Americans have far too short of memories if they think a major workplace-meets-social-strife shakedown can’t happen here.

He recalls that some of the motivation for the Occupy Wall Street movement beginning in 2011 over market-fueled wealth inequality stemmed from the pro-democracy and violent Arab Spring. The growth of the Black Lives Matter movement in the past several years, which even corporate America has selectively taken up, has its foundation through protest.

A little girl holds up a sign as “Black Lives Matter” New York protesters demonstrate in Times Square in June 2020 over the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer.

AFP via Getty Images

“When there are waves of protest at a certain scale they push out. The Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s U.S. pushed abroad, so it goes in both directions,” Winant said. “Americans are accustomed to representative democracy norms, and in many ways we have that. But we talk constantly about all the ways we don’t have that, including the [Jan. 6, 2021] attack on the Capitol over the election. We finger point at other countries when it happens here.”

In fact, he said, the groundswell of discord could well mean that the U.S. experiences protests on the level of those seen in Europe and the Middle East sometime over the next few years.

“There is a version of this,” he says. “It may be racial in the U.S., or take on a different edge.”