American football coaches are notorious for putting their teams in “prevent defense” mode when they’re leading near the end of a game and aim to keep the other team from putting a winning field goal or touchdown on the scoreboard.

For example, a team might use five, six or even seven defensive backs to thwart long pass completions.

The tactic sometimes works. Often it doesn’t, as the opposing team completes a rapid sequence of modest-yardage plays to win the game. Cynics say that the only thing a prevent defense prevents is your team winning the game.

A lot of modern investment strategies remind me of the prevent-defense — seemingly safe in the short run but costly in the long run. For example, mean-variance analysis and the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) both have been justifiably celebrated (indeed, rewarded with Nobel prizes) for their elegant mathematics and compelling insights, including the value of portfolio diversification and the importance of correlations among asset returns.

Yet they are value-agnostic strategies that ignore and undermine the insights of value investing. Even worse, they gauge risk by short-term fluctuations in market prices.

When a company is privately owned, potential buyers focus on the same things value investors focus on with publicly traded corporations — the company’s assets, profits and cash flow. They gauge risk by the confidence they have in their long-run projections of the company’s profits.

Yet once a company becomes publicly traded, too many investors fixate on annual, monthly, even daily fluctuations in market prices.

This misplaced focus not only distorts the choice of individual stocks, it also warps the allocation of investments between stocks and bonds, most obviously in 60/40, target-date, and having your age-in-bonds strategies.

A 60/40 strategy is 60% stocks and 40% bonds. A target-date strategy selects a target retirement date and shifts from stocks to bonds as that date nears. For example, I recently received a letter from my employer’s retirement plan stating that the plan’s default investment option is a target fund that invests 90% in stocks and 10% in bonds until the investor is 40 years old, shifts gradually to 30% equites and 70% fixed income over the next 30 years, and stays at 30/70 after that. An age-in-bonds strategy is what it sounds like: 40% bonds for a 40-year-old, 60% bonds for a 60-year-old, and so on.

The motivation for each of these strategies is to reap the higher returns from stocks while using bonds to cushion short-term volatility. Yet damping short-term volatility is like prevent defense in football — seeking short-run safety and sacrificing long-run success.

Consider a 50-year-old whose salary more than covers living expenses, who expects to work for many more years, is earning substantial income from a stock portfolio, and will receive Social Security benefits at some point. A 50% bond portfolio is likely to reduce the eventual bequest substantially and makes it more likely that this person will outlive his or her wealth. As this person becomes 60, 70, 80 years old and switches to 60%, 70%, 80% bonds, the costs will be even higher.

Another example. Unless they are literally running out of money to pay their bills, it does not make sense for 90-year-olds to have portfolios that are 10% invested in stocks, which will be converted to 40%, 50% or even 60% stocks when they die and bequeath their portfolios to their children.

There are some situations in which a 100% stock portfolio is genuinely risky — you need to liquidate your portfolio soon to buy a house or pay for your children’s college expenses — but a universal 60/40, target-retirement, or age-in-bonds strategy is surely a bad idea for many, if not most, people.

Let’s see how such strategies would have fared historically. This past December, Congress increased the age at which required minimum distributions (RMDs) must begin to 73. It is likely to go even higher in the future as life expectancies increase.

Consider against that backdrop a monthly investment in stocks and bonds in a retirement fund, beginning at age 25 and continuing for 50 years, until age 75. Assume that the monthly investment is initially $ 100 and grows by 5% annually.

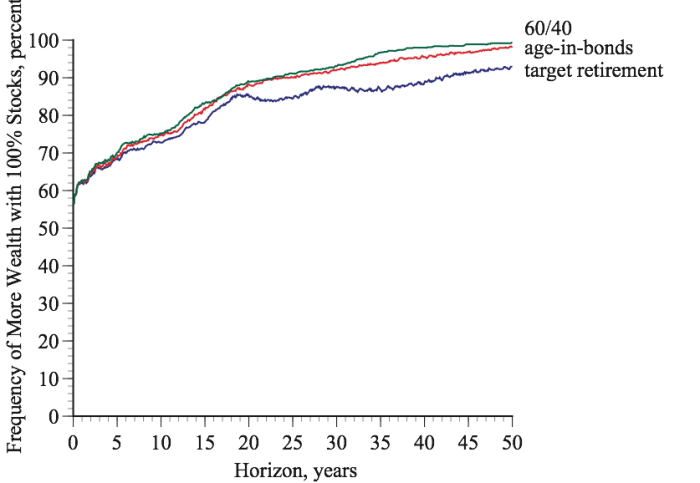

I looked at all possible starting dates in the historical data, as far back as the data go, to January 1926. The first figure shows how often a 100% stock strategy did better than three prevent-defense strategies for horizons ranging from one month to 50 years. Over 30-year horizons, the all-stock strategy beat the target-return, age-in-bonds, and 60/40 strategies 88%, 92%, and 93% of the time, respectively. Over 50-year horizons, stocks won 93%, 98%, and 99% of the time.

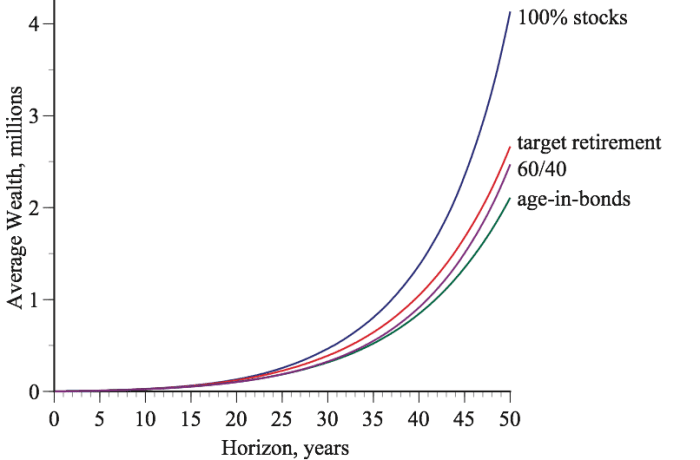

How much did this matter? A lot. The figure below shows the average wealth over various horizons up to 50 years. The all-stock strategy wound up with an average of $ 4.13 million after 50 years, compared to $ 2.67 million for the most successful prevent-defense strategy.

The past is no guarantee of the future, of course. Indeed, the whole point of a value-investing perspective is to think about the future, not the past. When I compare stocks with bonds currently and looking forward, stocks generally look like a better long-run investment — just as they have been in the past.

The current yield on 30-year Treasury bonds US00, +1.22% is around 3.8%, which is a reasonable estimate of the long-return from bonds unless future coupons are reinvested at significantly higher or lower interest rates. The current S&P 500 SPX, -1.10% dividends-plus-buybacks yield is around 5%. If dividends plus buybacks increase over time, the long-run return from stocks will be even higher — perhaps substantially higher. With 5% growth in the economy and corporate disbursements, the long-run return from stocks would be close to double digits, as it has been in the past.

For long-term investors who can largely ignore short-term price volatility, it is hard to see how a prevent-defense investment strategy is good for anything other than preventing your financial victory.

Gary Smith, Fletcher Jones Professor of Economics at Pomona College, is the author of dozens of research articles and 16 books, most recently, Distrust: Big Data, Data-Torturing, and the Assault on Science, Oxford University Press, 2023

More: Stocks won’t make you big money over the next decade, but they’re your best bet to beat inflation. The guru of index investing explains why.

Also read: Beating the stock market over time is next to impossible, but you should still try.