Birthrates in the United States have been declining since the Great Recession, and many expected that COVID-19 might accelerate this decline. And, indeed, birthrates early in the pandemic did drop substantially. However, when the economy swiftly recovered from COVID, birthrates ticked up in 2021, the first increase since 2014 (see Figure 1).

The question is whether the recent rise in birthrates represents a permanent increase in the total number of children women will end up having or simply reflects a shift in the timing of births. Two factors can shed some light on this question: 1) the ages at which the rises in birthrates occurred; and 2) any changes in fertility expectations.

Read: U.S. life expectancy has declined. What does that mean for your retirement?

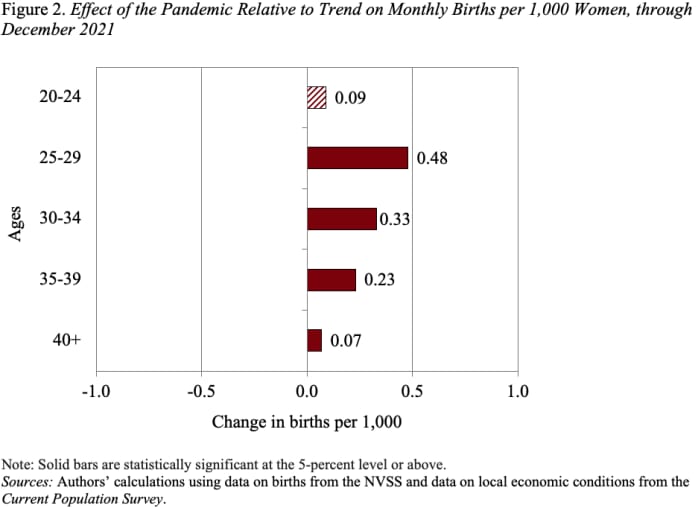

In terms of the age distribution, Figure 2 shows that monthly births per 1,000 women were higher for almost all ages at the end of 2021 than in similar months prepandemic. For women 40+, and to some extent women ages 35-39, the increase will have limited impact on aggregate completed fertility, since these groups account for only 20% of total births. The more relevant groups are women in their 20s and early 30s, who count for the bulk of births. For these groups, the question is whether the uptick is temporary or permanent.

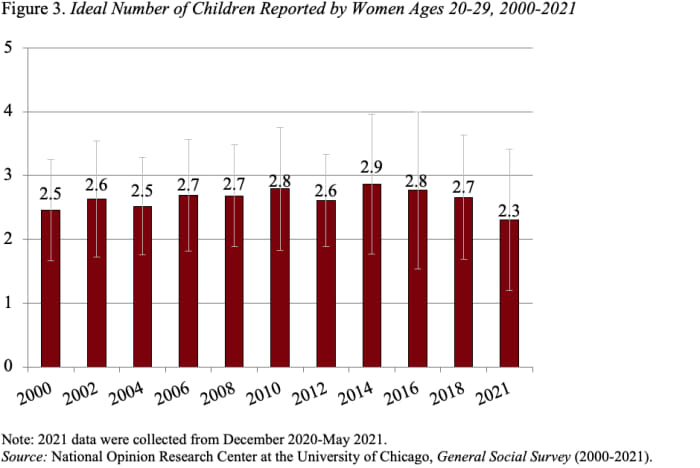

Some early polling data — albeit for a relatively small sample — suggest that the number of children that women in their 20s view as ideal plummeted in 2021 (see Figure 3). That is, despite the small uptick in births during the pandemic, women in their 20s now want fewer children than they did prepandemic.

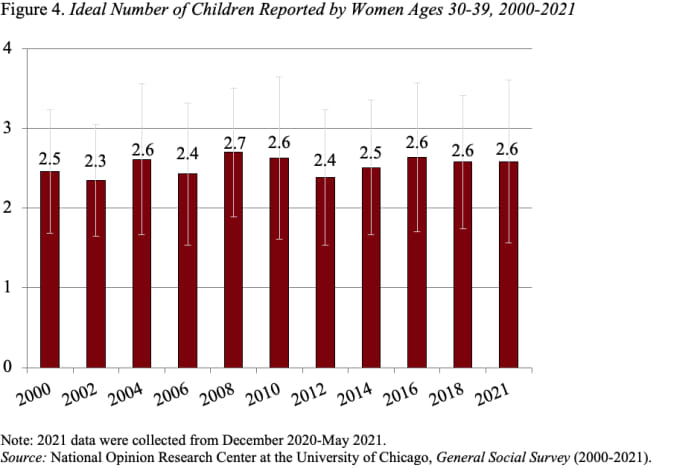

In contrast, the fertility expectations of women in their 30s did not change, suggesting that the pandemic increase reflects shifts in timing for this group rather than a change in the total number of children they will have (see Figure 4). (Women in their early 30s are the key group of interest; since it was not feasible to break the data out separately for them in this case, the assumption is that the overall pattern for those in their 30s applies to them as well.)

In short, if the overall pattern of declining fertility expectations — driven by women 20-29 — holds in more comprehensive surveys, completed fertility is likely to continue to fall. And while the shift to fewer children may be a positive reflection of the opportunities offered today’s women, it will also result in a smaller workforce, slower economic growth, and higher required tax rates for pay-as-you-go programs such as Social Security.