For months, the bond market has flashed multiple warnings that a U.S. recession could be on the way, a view that many in financial markets have finally accepted.

One of them is the 10-year minus 3-month Treasury yield spread, which has been below zero since late October, but hasn’t been negative for long enough to send a definitive statement about a pending economic contraction. Now Campbell Harvey, the Duke University finance professor who pioneered the use of that spread as a predictive tool, says the gauge may be sending a “false signal, which is interesting because I’m the one who invented the indicator.”

The surprising conclusion from Harvey, whose 1986 dissertation at the University of Chicago linked the difference between longer- and shorter-term interest rates to future U.S. economic growth, comes at a time when the broader financial market has been fretting about a possible economic downturn in 2023.

On Tuesday, U.S. stocks DJIA, +0.51% SPX, +0.33% were attempting to recover from four straight days of declines — as well as back-to-back weekly losses — as investors weighed recession fears and a surprising policy shift by the Bank of Japan. Within the bond market, 44 different yield spreads were negative as of Monday, according to Dow Jones Market Data — a sign of pessimism on the economic outlook.

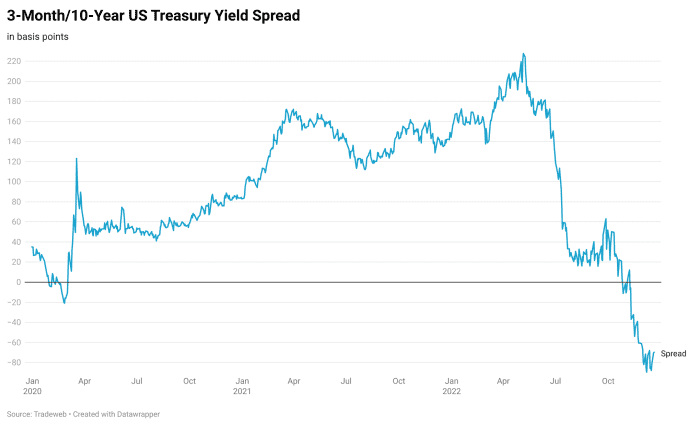

The spread between rates on the 3-month bill TMUBMUSD03M, 4.305% and 10-year note has been negative for almost two months — a reflection of a 10-year rate trading well below its 3-month counterpart — and was around minus 61 basis points on Tuesday. Such inversions have preceded eight out of the past eight recessions. The counterpart spread between 2- BX:TMUBMUSD02Y and 10-year yields BX:TMUBMUSD10Y has been consistently below zero for almost six months, though it has emitted at least one false signal in the past, according to Harvey.

In an interview with MarketWatch, Harvey, a Canadian-born economist, said that one reason for his current view is that the 3-month/10-year spread as a model “is so well known now that it has impacted behavior,” causing both companies and consumers to become more cautious — a form of “risk management” that “makes the probability of a soft-landing more likely.”

“We’re in a period of slow growth, which is consistent with the model, but as far as recession, I’m skeptical of that. A hard landing is unlikely,” he said via phone, though he didn’t rule out the possibility of a mild downturn. “What I’m saying is straightforward. This is a valuable indicator and I believe it is accurate in forecasting slowing economic growth. In terms of a hard landing, you need to look at other information.”

Source: Tradeweb

Ordinarily, Treasury spreads should be widening and sloping upward, not downward, as investors take into account brighter growth prospects and seek additional compensation for holding a bond or note for a longer period. They’ve been shrinking below zero, or inverting, as the Federal Reserve continues to hike interest rates and investors factor in the likely impact of those moves down the road.

On Oct. 26, the 3-month/10-year spread finished the U.S. trading session below zero for the first time since March 2, 2020. At the time, Harvey said he would need to see the spread stay below zero through December to be confident that a recession is on the way. It’s not yet reached that marker, with less than two weeks still left in the year.

Here are the reasons the professor is now citing for why the spread may not be as reliable an indicator of an approaching recession this time around, though it’s clearly pointing in the direction of “lethargic” economic growth:

- Unusual employment situation. While unemployment is low before every recession, it is unusual to have as much excess demand for labor as the U.S. does now. “This means laid off workers can find work quickly.”

- Technology-driven layoffs. Laid-off workers from companies like Meta Platforms Inc. META, +1.99%, the parent of Facebook, and Twitter “are highly skilled and have very short duration of unemployment,” in contrast to the 2007-2008 global financial crisis and brief 2020 COVID recession, which captured a broader set of workers from other industries.

- Strong consumers and financial institutions. Consumers and the financial sector are stronger than they were before. That makes it less likely that a drop in housing prices will cause a contagion, or that any problems in the financial sector might spread rapidly across the economy, Harvey said.

- Inflation-adjusted yields. Harvey focuses on inflation-adjusted yields because they better reflect the real economic outlook. “Once we inflation adjust the yields, the yield curve is not inverted — but it is flat (associated with lower growth but not necessarily a recession),” he said.

- Adjustments in behavior. Because of the inverted yield curve, companies are unlikely to “bet the firm” on a big investment project plus consumers are being cautious and have plenty of savings, according to Harvey. “All of this leads to the self-fulfilling prophesy – i.e., lower growth. However, you can also view it as risk management. Even if growth slows, companies can make it through without massive layoffs.”