The six stocks that are being added to the Nasdaq 100 index NDX, -0.89% barely rose, on average, after their additions were announced.

Nasdaq Inc. announced the change after the close of trading on Dec. 9. From their closing prices that day (before the announcement) to their opening prices on Monday (three days later), the six stocks added to the NDX declined a fraction of a percent on average at the open.

(Note that this period over which I calculated their return is the appropriate one for measuring the impact of Nasdaq’s announcement. Later in Monday’s trading session, as the broad market staged a sizeable rally, so did some of these stocks slated to be added to the NDX. But it’s not clear that we can attribute their post-open gains to Nasdaq’s announcement last Friday.)

It’s a big surprise that these stocks didn’t do a lot better. In past years, index additions tended to experience a sizeable jump in the immediate wake of their additions being announced.

Perhaps even more surprising is that the stocks that Nasdaq is dumping from the NDX barely declined at the open — just 31 basis points, or 0.31%, on average. It used to be that stocks dumped from a major index suffered significantly more than the added stocks gained.

Yet no one should be surprised that these stocks barely reacted, according to a new study from two Harvard professors. They found that the price impact of index additions and deletions has been declining for a number of years now.

The study, “The Disappearing Index Effect,” was conducted by Robin Greenwood, a professor of finance and banking at Harvard Business School, and Marco Sammon, an assistant finance professor at that institution. They examined all additions and deletions to the S&P 500 SPX, -1.11% since 1980.

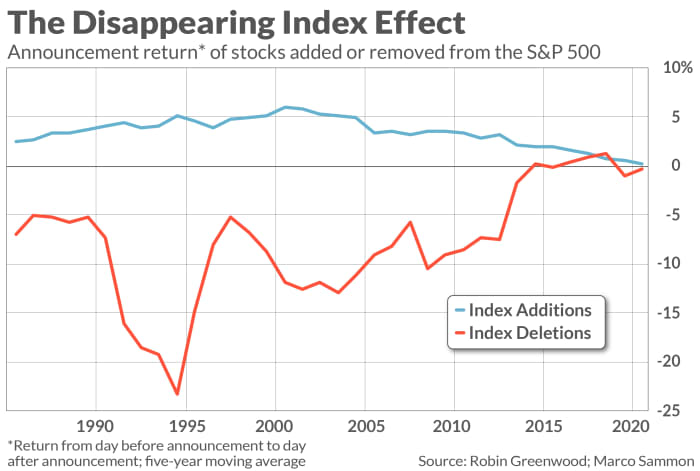

The chart below plots the trends in these stocks’ so-called announcement returns — their gains from the day before their additions or deletions were announced to the day after.

Notice that additions’ announcement returns gradually increased throughout the 1980s and 1990s, with the five-year moving average of their returns reaching a peak in 2000. Since then their average return has gradually declined, and the more recent data show it to be statistically indistinguishable from zero.

Deletions follow a largely similar pattern, though in reverse. Their average announcement return declined during the 1980s and early 1990s, with the five-year moving average reaching a low in 1994 of minus 23.2%. Since then deletions’ announcement return has gradually lessened, and is today statistically indistinguishable from zero.

Though the study focused only on the S&P 500, Greenwood in an interview said that a similar pattern appears to exist for additions and deletions to other widely followed stock market benchmarks.

Why has the index effect disappeared?

The researchers believe that a number of factors have combined to cause the index effect to first shrink and then disappear. One is increased market liquidity, because of which a greater dollar amount of the typical stock can be bought or sold without having a significant price impact. Another is the increase in the number of S&P 500 additions and deletions that represent “migrations” to and from other major indexes. In such a case, the additional demand created by an index addition may be largely offset by the additional supply caused by another index’s deletion.

The takeaway, Greenwood told me, is that market-beating strategies don’t last forever. Because the index effect used to be large and predictable, it was inevitable that Wall Street would eventually discover it and, in the process, kill the goose laying the golden egg. He and his-co-author write: “The decline of the index effect is much like the evidence for other anomalies [patterns that can be profitably exploited], that they decline once they are well recognized by the market.”

This overall investment lesson is one of the most important takeaways of this new study, even if you never thought of trying to trade the index effect yourself. No matter what strategy you are currently pursuing, and no matter how profitable it has been in the past, you should not count on its profitability persisting indefinitely.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: This little-known but spot-on economic indicator says recession and lower stock prices are all but certain

Plus: Why stock-market investors shouldn’t count on a ‘Santa Claus’ rally this year