Credit crises are lurking in every corner of emerging markets and the latest scares are no less dramatic. (Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg)

Global investors who had enough of Chinese real estate developers’ default drama have been looking for safe havens elsewhere. They are coming away feeling disappointed. Credit crises are lurking in every corner of emerging markets and the latest scares are no less dramatic.

Earlier this month, South Korea’s Heungkuk Life Insurance Co. rattled the bond investors with a surprise decision not to call its $ 500 million perpetual note. Panic selling spread well beyond Seoul. Even perpetuals issued by Hong Kong-listed AIA Group, a well-run insurer with A+ rating from S&P Global Ratings, tumbled.

The obscure Korean insurer had opened a Pandora’s Box. It challenged an unspoken market convention that financial companies would always redeem their perpetuals on their first call date, even if the decision makes no economic sense. Heungkuk changed its mind a week later amid a broader selloff.

As Heungkuk’s drama was playing out, investors started to ask whether Korea, a usually quiet space where about 76 percent of outstanding credit is rated single-A and above, is seeing a crunch too. Legoland Korea, a theme park operator, defaulted on its commercial paper in late September; the nation’s corporate bond market shrank the most on record in October; and corporate credit spreads are at the highest in a decade. Heungkuk’s surprise move may well be a sign that just like Chinese companies, Korea Inc. is losing access to refinance its borrowings.

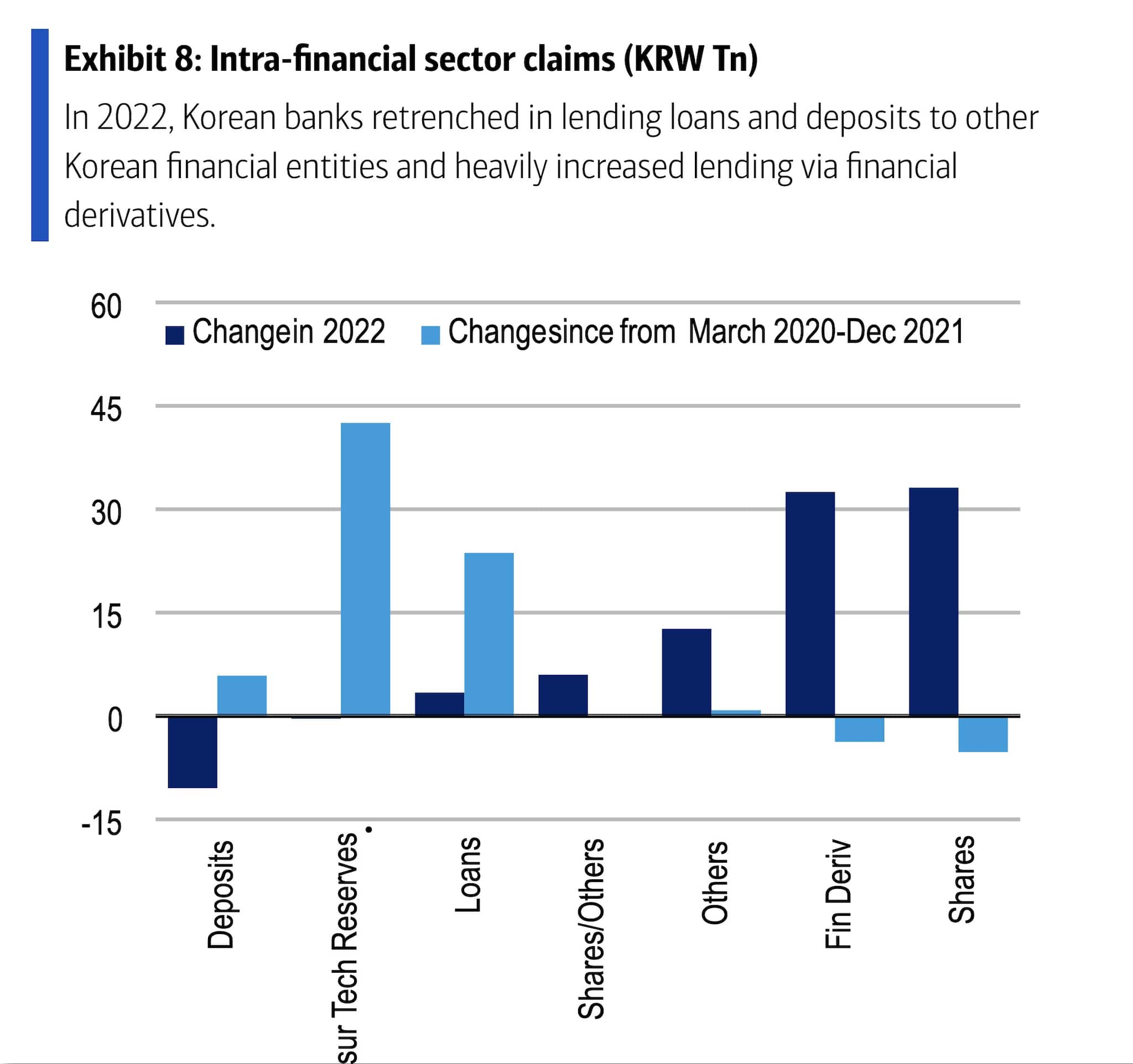

At the heart of Korea’s emerging credit crisis appears to be a funding issue. In April 2020, regulators allowed banks to relax their liquidity coverage ratios so they could boost lending to the COVID-19-stricken economy. But as South Korea reopened and Seoul unwound its emergency measures, banks have been left scrambling for funding, offering higher rates for time deposits and changing the way they lend. Credit for the insurance sector, for one, is seeing a drastic slowdown, according to data compiled by Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

Vietnam, often hailed as the next China, is seeing its own version of a developer scare. Builders are struggling to obtain loans and sell bonds following the detention in early October of Truong My Lan, the chairwoman of real estate conglomerate Van Thinh Phat Holdings Group. A convertible issue by No Va Land Investment Group tumbled on media reports that the country’s second-largest listed builder is restructuring its business.

When I was on a reporting trip there in August, it became evident that, just like China, Vietnam was forming its own property bubble, and that a regulatory crackdown was in the works. From people’s love for real estate, to the practice of pre-sales, to developers’ poor corporate governance, Vietnam shares too many similarities with China for Hanoi’s comfort.

This perhaps explains why investors are crowding back to Chinese developers as soon as there is any concrete news of Beijing’s support. For those looking to bottom fish, dollar bonds issued by Chinese high-yield builders have already lost two-thirds of their value this year. Meanwhile, the rest of emerging markets do not look any prettier.

For years, global investors knew the likes of China Evergrande Group were swimming naked. What they did not know, and are starting to find out, is that many other developing nations are as audacious swimmers as the Chinese builders.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. Views are personal, and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Credit: Bloomberg