“Let’s define busy” read a memo circulated to rookie investment bankers at Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette in the mid-1990s. “You are busy if you are working each weekday at least 16 hours and at least 16 hours on the weekend. These are working hours—not travelling, gabbing or eating time. If these are not your hours at the office, you have the capacity to take on more work.”

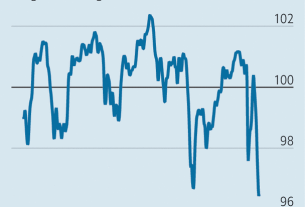

Today’s bankers are more than willing to put in the hours—the problem is they lack the work to fill them. The fee-bonanza caused by cheap money and giddy corporate bosses is long gone. Dealmaking revenues at the largest banks are down by almost half this year, and pipelines are nowhere near full. As revenues normalise, so do attitudes to hiring and firing. Last week Goldman Sachs, an American bank, began its annual cull of between 1% and 5% of staff, for the first time since 2019. An industry-wide hiring binge during the covid-19 pandemic means lay-offs will probably extend well beyond spring-cleaning. Wall Street’s human-resources departments will finally get to do the job they signed up for: sticking it to the salaried rich.

First for the chop are the underperformers. Think expensive senior dealmakers with rusty Rolodexes and the occasional knackered junior Excel-jockey. After that, choosing whom to show the door becomes an exercise in predicting where the market is going. “A real danger is over-firing and missing a bounce-back in activity as some banks did after the dotcom crash,” notes Jon Peace, a banking analyst at Credit Suisse.

Equity capital markets bankers will find themselves near the top of the hit-list. They are having a rotten year: the number of initial public offerings in America is down nearly 90%. Few firms risk listing their shares while markets roil and chief-executive confidence is touching 40-year lows. Special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs), blank-cheque vehicles which raise money by listing on a stockmarket, are a distant memory. Bankers who made a killing in the frothiest industries and structures are most at risk. Those who have retained even a tangential connection to the real economy will be looking to Frankfurt this week, hoping to convince the higher-ups that the blockbuster listing of Porsche, a carmaker, is a first breath rather than a last gasp for equity issuance. It only takes one deal to save a career.

Bankers who toil in service of private-equity funds may overestimate their chances of survival—buy-out volumes have proved resilient and funds have mountains of capital waiting to be deployed. But when the masters of the universe come knocking, it tends to be in search of leverage, not advice. The uncomfortable truth is that big banks now mainly get paid for flogging junk debt, not the heaps of PowerPoint-philosophy they wantonly produce. Bankers involved in the buy-out of Citrix, an American technology firm, are finding this out while offloading debt to the market at an eye-watering loss. Appetite to fund similar deals is waning. Any banker incapable of persuading their boss that private-equity funds will continue to seek their counsel without the draw of billions in financing is in trouble.

If the outlook remains gloomy, remember the epigram of the mergers and acquisitions banker: to each problem, a deal. Spin-offs, rather than lay-offs, might be the answer. At scandal-ridden, Paradeplatz-prince Credit Suisse, the investment bank is the worst-performing part. Faced with itchy investors—the firm’s share price is down nearly 60% this year—bosses are cooking up something radical ahead of their results in October. Spinning off the entire investment bank is unlikely, but asset sales of profitable parts of the bank are being considered. Credit Suisse, which has long punched above its weight in lending to risky companies, will learn the true price of its advice if it fully commits to offering a “capital-light, advisory-led” investment bank.

In the event that suggestions from the human-resources and investment-banking departments do not turn things around, maybe the folks in marketing have a plan? Turning back the clock might not be a bad idea. Credit Suisse may revive the First Boston brand, the name of the revered American investment bank it acquired in 1990. Names cannot lower interest rates, but there is a part of every banker at boring Barclays and UBS who would love to resurrect the Lehman or Warburg monikers. If they must be shown the door, at least let them leave with a little old-school swagger.