OMICRON MOVES fast. That makes it difficult to contain—even for China, which tries to stomp promptly on any outbreak. A cluster of infections in Shanghai, for example, has shattered the city’s reputation for deft handling of the pandemic, forcing the government to impose a staggered lockdown, of uncertain duration, for which it seems surprisingly ill prepared.

The variant’s speed also means that China’s economic prospects are unusually hard to track. A lot can happen in the time between a data point’s release and its reference period. The most recent hard numbers on China’s economy refer to the two months of January and February. Those (surprisingly good) figures already look dated, even quaint. For much of that period, there was no war in Europe. And new covid-19 cases in mainland China averaged fewer than 200 per day, compared with the 13,267 infections reported on April 4th. Relying on these official economic figures is like using a rear-view mirror to steer through a chicane.

For a more timely take on China’s fast-deteriorating economy, some analysts are turning to less conventional indicators. For example, Baidu, a popular search engine and mapping tool, provides a daily mobility index, based on tracking the movement of smartphones. Over the seven days to April 3rd, this index was more than 48% below its level a year ago.

The Baidu index is best suited to tracking movement between cities, says Ting Lu of Nomura, a bank. To gauge the hustle and bustle within cities, he uses other indicators, such as subway trips. Over the week ending April 2nd, the number of metro journeys in eight big Chinese cities was nearly 34% below its level from a year ago. In locked-down Shanghai, where many subway lines are now closed, the number of trips was down by nearly 93%, a worse drop than the city suffered in early 2020.

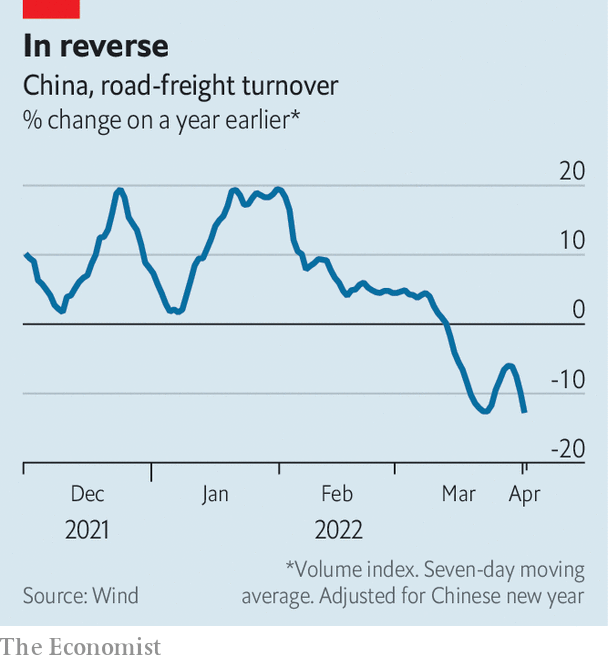

The two numbers that worry Mr Lu the most track the economy’s distribution system, specifically couriers and lorries. In the week ending April 1st, an index of express deliveries by courier companies was nearly 27% below its level at a similar point last year. Over the same period, an index of road freight compiled by Wind, a data provider, shows a fall of 12.8%. The decline looks especially stark because this indicator was increasing by more than 7% at the end of last year.

Unconventional indicators are all the more valuable in China because of doubts about the official data. The strong figures for January and February, for example, are not only old but odd. They suggest that investment in “fixed” assets, like infrastructure, manufacturing facilities and property, grew by 12.2% in nominal terms, compared with a year earlier. But that is hard to square with double-digit declines in the output of steel and cement. The recovery in property investment also looks peculiar alongside the fall in housing sales, starts and land purchases. When local governments in the provinces of Shanxi, Guizhou and Inner Mongolia said that they were double-checking their figures at the behest of the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) it became clear that the official statistics look odd even to the official statisticians.

China’s high-frequency indicators proved their worth in the spring of 2020, during the fog of the early pandemic. Although everyone knew the economy would suffer, forecasters were at first timid in cutting their growth forecasts. No one knew exactly how the economy would react or what the NBS would be prepared to report. With the accumulation of evidence from high-frequency data, forecasters were eventually brave enough to predict negative growth for the first quarter of 2020. Indeed, GDP shrank by 6.8%, according to even the official figures.

The timeliness of these indicators makes them valuable in periods of flux. But they must still be interpreted with care. “There are many traps in those numbers,” says Mr Lu. Any short period of seven days can be distorted by idiosyncratic events, such as bad weather or holidays. And annual growth rates can be skewed by similar idiosyncrasies a year ago. Moreover, many of these indicators have a history of only a couple of years. Interpreting them is therefore more art than science. What does a dramatic weekly decline in road freight mean for quarterly GDP growth? It is impossible to say with any precision. Mr Lu was heavily trained in econometrics when he was a phd student at the University of California, Berkeley. “But with only one or two years of data, if I used the kind of techniques I learned at school, people would laugh at me.”

To help avoid some of the traps lurking in these unconventional indicators, Mr Lu and his team watch “a bunch of numbers, instead of just one”. In a recent report he highlighted 20 indicators, ranging from asphalt production to movie-ticket sales. “If seven or eight out of ten indicators are worsening, then we can be confident that GDP growth is getting worse,” he says. Right now, he thinks, the direction is clear. “Something must be going very wrong.”

For more expert analysis of the biggest stories in economics, business and markets, sign up to Money Talks, our weekly newsletter.

Dig deeper

All our stories relating to the pandemic can be found on our coronavirus hub.