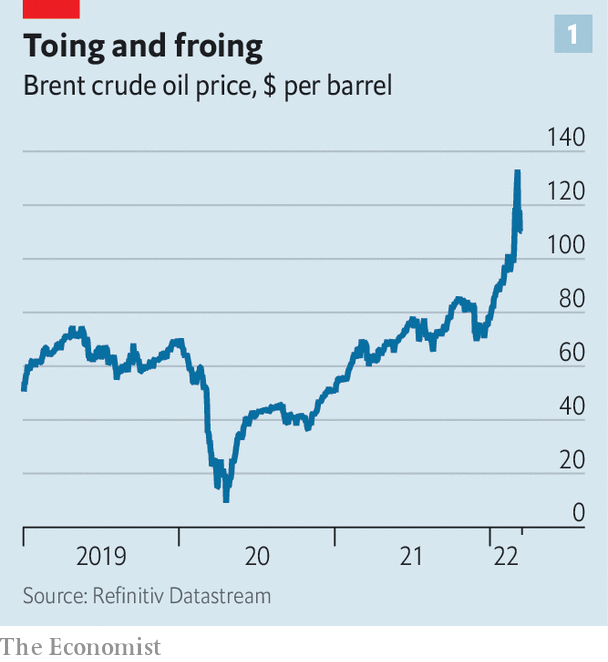

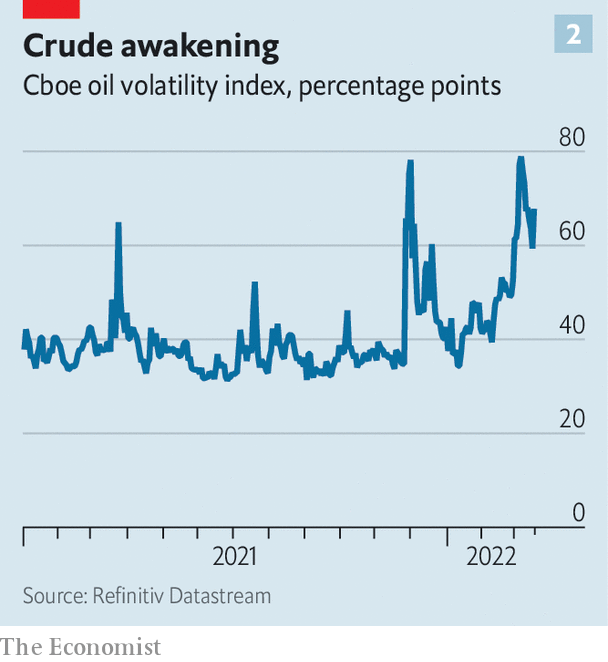

ALMOST A MONTH after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sent the oil price surging, the turbulence in one of the world’s most crucial commodities markets shows little sign of coming to an end. The price of a barrel of Brent crude oil was around $ 108 on March 18th, still higher than its level when the war began, of about $ 94. But over the past fortnight it has whipsawed from a peak of $ 128 to as low as $ 98. The pandemic-related chaos of 2020 aside, the OVX index of oil-market volatility has rarely been higher in the past decade than it has been this month.

The swings reflect the interplay between the geopolitical and economic forces buffeting the world today, from war to rising interest rates and covid-19. Even beyond the outcome of the conflict in Ukraine, there are three big sources of uncertainty for the oil market.

The first is what the members of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) do as the West’s sanctions bite and Russian production is shunned. America has banned imports of Russian oil; even in countries that have not taken the same step, prospective buyers are struggling to transact with the Russian financial intermediaries that have been cut off from the plumbing of global finance as a result of sanctions, and may fear fresh sanctions to come.

On March 16th the International Energy Agency, an industry forecaster, said that international markets could face a shortfall of 3m barrels of oil per day from April as a consequence. (The world consumed about 98m barrels a day last year.) The disruption in what was once a fluid global market is best illustrated by the gap between the prices of the Brent benchmark and Urals oil. On January 31st it stood at about 60 cents per barrel. By March 18th it had widened to nearly $ 30.

This leaves a great deal of power in the hands of the two countries that are most able to offset a chunk of the Russian shortfall: Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. So far, both have resisted pleas to raise output substantially. At a meeting in early March, OPEC and its allies (including Russia) merely confirmed their existing plans to raise overall output by 400,000 barrels per day. Their next gathering, at the end of this month, will be watched closely. With so much influence in the hands of two governments in particular, even small shifts in public pronouncements have the potential to set off swings in the oil price.

The second seam of uncertainty relates to the capacity of American shale-oil production to meet the supply shortfall. During the first fracking boom, which lasted from around 2010 to 2015, American output surged, causing the oil price to slump and weakening OPEC‘s hand. But conditions in the American economy have changed dramatically since, leaving analysts and industry insiders doubtful that shale can rise to the challenge.

For a start, financing conditions are less encouraging than they were during the production boom in 2010-15. The Federal Reserve is expected to raise interest rates several times this year and next: two-year Treasury yields are just shy of 2%, compared with the sub-1% levels that persisted during most of the past boom. Another constraint on production comes from America’s tight labour market. There were just over 128,000 people employed in oil-and-gas extraction in America in February, down from more than 200,000 in late 2014. With the headline unemployment rate at 3.8% and employers struggling to fill existing vacancies already, finding several tens of thousands of workers to move across the country will be no mean feat.

The industry’s attitudes have also shifted. Both American producers and their potential creditors are now far more cautious about borrowing. Banks and asset managers are bound by stricter environmental standards. That is one factor driving costs higher. In the final quarter of last year, energy-exploration and production firms reported the steepest increase in lease-operating expenses (ie, the recurring costs of operating wells) in at least six years, according to a survey by the Dallas Fed. Drillers themselves, having struggled to make consistent profits in the past, are far keener on capital discipline this time, too.

The third and perhaps most vexing component of the volatility in the oil price is to do with demand. China’s “zero-covid” strategy is being tested to an extreme degree. The country has recorded its highest numbers of cases since the pandemic began, and tens of millions of people are locked down in Shanghai and Shenzhen, two prosperous cities and important export hubs. Platts Analytics, a commodities-research house, suggests that the restrictions could cut oil demand by 650,000 barrels per day in March, roughly equivalent to Venezuela’s oil output.

Even before the lockdowns began, there were worrying signs of a slowdown in China’s economy, particularly in the property sector. Land-sales revenue, the fuel on which Chinese local governments run, plunged by 30%, year on year, in January and February. The Hang Seng Mainland Properties Index of developers’ stocks recently touched a near-five-year low, and has declined by around 50% since the start of the pandemic. The authorities, meanwhile, are torn between their campaign to rein in leverage in the property sector, and their desire to keep the economy growing at a steady clip. Any sign that the slowdown in the world’s biggest importer of energy is becoming broad-based would mean more tumult in commodities markets.

The machinations of OPEC, the shale calculus in America, and the health of the Chinese economy: if the heightened volatility in the oil market is to recede, then these sources of uncertainty will have to abate. Any one of these factors would usually be sufficient to generate wild price swings. Together, they make a volatile mix.

For more expert analysis of the biggest stories in economics, business and markets, sign up to Money Talks, our weekly newsletter.