Hello and welcome back to MarketWatch’s Extra Credit column, a look at the news through the lens of debt.

This week we’re first to report on a lawsuit filed by nine borrowers over the way they were treated after they defaulted on their student loans.

When Catherine Assanah’s tax refund didn’t show up in her bank account in 2018, she became concerned. The Brooklyn mother had plans to use the $ 6,816 to buy food for her two children, catch up on back rent payments and purchase a pair of sneakers for her son, who was walking around in worn out shoes.

Assanah began searching for her missing refund, made up mostly of the Earned Income Tax Credit, an anti-poverty measure that supplements the income of low- and moderate-income workers and families. She first talked to her tax preparer and then placed a call to the IRS. The tax agency informed Assanah that the government took her money to repay a student loan she’d defaulted on the year before.

“I felt so very disappointed,” Assanah recalled upon learning the news. Of her son, she said, “he had to wear the sneakers with the hole in the bottom.”

What Assanah didn’t know at the time was that she had the right to cure her default — and save her tax refund — by consolidating her loans. The relatively quick process could have been completed online and moved her immediately into an affordable repayment plan. If Assanah had known to complete the consolidation process before the government seized her refund, she likely would have been able to keep it.

Now, she’s one of nine plaintiffs suing the Department of Education, the Treasury Department and two companies that work with the government in collecting on defaulted student loans. The lawsuit accuses the government and its contractors of not properly communicating with defaulted borrowers, including in phone calls and notices mailed to borrowers’ homes, and failing to provide them with information about their right to consolidate out of default. Instead, the suit alleges, they often steer these borrowers towards another route for getting out of default called rehabilitation, a process that takes several months and includes multiple ways for borrowers to fall off the path towards being current.

The result of pushing borrowers towards rehabilitation is that borrowers like Assanah unnecessarily lose out on much-needed tax refunds and Social Security benefits, the suit claims. Rehabilitation is described in the lawsuit as a time consuming process consisting of required payments that borrowers in precarious financial situations may be hesitant to begin or struggle to complete. While a borrower is in the process of rehabilitating their loan, they can still be subject to collection actions, like having their tax refund or Social Security benefit seized.

For Assanah, losing out on a tax refund over a defaulted student loan was particularly frustrating because she hadn’t borrowed that money willingly. In 2010, she signed up for courses at a campus of the now-defunct for-profit college Sanford-Brown in hopes of becoming an anesthesiology technician. Assanah was lured to the school by television commercials and a recruiter’s assurance that she wouldn’t have to pay anything to attend because her low income qualified her for financial aid. Instead, the college took out student loans on her behalf, according to court documents.

Assanah says she didn’t become aware of the loans until she started working with a credit counselor. By 2018, the debt she never asked for was threatening her much-needed tax refund. Assanah called the debt collector responsible for her student loans to see if she could fix the problem, but the company didn’t mention she could get out of default through consolidation, according to court documents. Shortly after, she received a letter from the company that did not mention either consolidation or rehabilitation.

“It seemed like there was nothing I could do,” she said.

Johnson M. Tyler, Assanah’s lawyer, said he decided to file the lawsuit on behalf of several borrowers after watching the “startling reaction” from clients whose loans he was able to make current through consolidation.

“They would come to me and they’d be like ‘I’ve gone through hell trying to deal with this,’” said Tyler, a senior consumer attorney at Brooklyn Legal Services. “And we would take care of it, literally in 20 minutes.” Tyler’s clients would wonder aloud why they hadn’t heard about this option earlier.

That’s what happened to Assanah. In 2021, after having a stroke that left her unable to work, the 49-year-old was still searching for a way to get out of default and protect future tax refunds. Ultimately, she found Tyler, who assisted her in consolidating her loans out of default. Even with his help, she was still concerned the process wouldn’t work because the information she received from official sources — the government and its hired debt collectors — never told her she could get out of default without making any payments first, according to court documents.

“I was treated unfairly by everyone that I had an encounter with,” including Sanford-Brown, the government and its debt collectors, she said. “It’s so very unfair,” she said, speaking through tears. “Give people a fair break instead of being so mean.”

Advocates and borrowers have complained about the student debt collection system for years

For years, consumer advocates and borrowers have complained that the broader approach to student debt collection can be draconian and counterproductive. They have pointed to the practice of not informing borrowers about their right to get out of default without making any payments and instead pushing them towards rehabilitation as a prime example. Federal student loan borrowers have the right to affordable repayment plans that can help them stay current on their debt, but once borrowers default, the government can use extraordinary powers to get its money back, including garnishing borrowers’ wages and taking their tax refunds or Social Security benefits.

Those programs are designed to keep people out of poverty — in the case of the Earned Income Tax Credit, it’s one of the government’s most successful anti-poverty measures. Offsetting these benefits could actually make it more difficult for borrowers to achieve the kind of financial stability that would allow them to make payments towards their loans, advocates say.

“It just piles on to the heinousness of our collection system,” Persis Yu, policy director and managing counsel at the Student Borrower Protection Center, an advocacy group, said of the practices highlighted in the lawsuit. “This is a system that is based upon punishing borrowers and we don’t take their rights as seriously as we need to.”

The rehabilitation suit comes as advocates and borrowers are watching to see how the Department of Education is going to treat defaulted borrowers going forward. Last year, the Department canceled all of its contracts with private collection agencies, the debt collectors the agency has historically used to recoup funds from defaulted borrowers. Richard Cordray, the chief operating officer of Federal Student Aid, said at the time that the decision was part of a “long-term strategy to improve defaulted federal student loan collections.”

When federal student loan payments and collections are scheduled to resume on May 1, FSA plans to transition the work of supporting defaulted borrowers to vendors with “extensive debt collection experience,” according to a Department spokesperson. These firms were awarded contracts through a competitive process in 2020 to manage consumer-facing and back office work related to student loan repayment.

In addition, Department officials are reportedly weighing bringing all defaulted borrowers current on their loans, through a program dubbed Fresh Start, once the pandemic-era payment pause on student loan payments and collections ends.

The Department of Education spokesperson declined to comment on pending litigation, but said in an email that “The Biden-Harris Administration is committed to improving outcomes for all student loan borrowers, including those in default.” That includes reviewing options for “how best to support borrowers in default when the payment pause ends,” and more broadly, the agency is “reviewing our collection policies and practices to look for ways to both keep borrowers out of default and to get borrowers in default back on track.”

Eileen Rivera, vice president for public relations and communications at Maximus, one of the Department’s contractors who was named in the suit, declined to comment on ongoing litigation.

“It is our standard practice to provide defaulted borrowers information on loan rehabilitation and consolidation, and, if borrowers request, we work with them on processes that are clearly outlined at StudentAid.gov,” Rivera wrote in an email.

The Treasury Department declined to comment.

Policymakers are aware that a common path out of default isn’t always the best

Policymakers have known for years that rehabilitation may not be the best path out of default for many borrowers and yet, historically, it’s often been the most common. In order for a borrower to successfully become current on their loan through rehabilitation they have to make nine payments on the debt within ten months.

The amount of these payments is based on a borrower’s income and can be as low as $ 5. Still, the time-consuming process features many opportunities for a borrower to be knocked off track, according to a 2016 report from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

““This is a system that is based upon punishing borrowers and we don’t take their rights as seriously as we need to.” ”

The agency found that borrowers faced obstacles, including communication breakdowns and paperwork processing problems, when trying to work with their debt collector to establish an affordable rehabilitation plan.

In the past, once a borrower completed a rehabilitation with their debt collector, their account was transferred to a student loan servicer, a company that works with borrowers who are current on their loans. The CFPB found that during this transition period servicers would throw up roadblocks to borrowers enrolling in an affordable repayment plan after curing their default — putting them at risk of becoming delinquent or even defaulting once again because they faced a high payment.

There can be downsides to consolidating for some borrowers. For example, their interest rate may be slightly higher and the unpaid interest on the loan will capitalize, meaning it is added to the principal. Still, for many borrowers it’s the quickest way to get out of default and offers the least risk of borrowers defaulting again because they can be immediately shuttled into an affordable repayment plan.

So if rehabilitation often isn’t the best choice for borrowers looking to get out of default, why are so many pushed towards it? For one, historically the government has paid debt collectors more for taking a borrower through the rehabilitation process — in some cases these companies earned as much as $ 40 for each dollar they recovered through rehabilitation, the CFPB said in 2016.

More broadly, the focus on rehabilitation is a vestige of an older student loan system. For decades most federal student loans were made by commercial lenders and backed by the government. As part of this system, non-profit or quasi-state organizations, known as guarantee agencies, insured the loans and took them over from the lender when a borrower defaulted. In order for a guarantee agency to complete a borrowers’ rehabilitation, they needed to find another lender to repurchase the loan. A history of monthly payments, as rehabilitation requires, could help convince a lender to do so.

In addition, the emphasis on rehabilitation pre-dates federal student loan borrowers’ widespread right to make affordable monthly payments. In the early 1990s, Congress directed guarantee agencies to allow borrowers to get out of default through a rehabilitation where they made reasonable and affordable payments.

Now, all borrowers, whether in default or not, have the right to make payments as a percentage of their income. That means that for many borrowers, consolidating straight into a current student loan and income-driven repayment plan can be a better option for getting out of default than spending the nine months making rehabilitation payments.

“For a long time there had been this assumption that somehow rehabilitation had better outcomes,” Yu said. “There’s this very ethics-driven,” mentality that “people need to get into the habit of making payments. The reality is that the data doesn’t show that that’s true.”

In addition to putting borrowers at risk of defaulting again, the prolonged nature of rehabilitation means that borrowers can be in the midst of the process and still lose out on their government benefits.

Made nine payments but still lost his tax refund

In 2018, Saibou Sidibe, one of the other plaintiffs in the rehabilitation lawsuit filed by Tyler, received a notice from the Department of Education that his tax refund was at risk of being offset over defaulted student loans.

Sidibe, who immigrated to the U.S. from the Ivory Coast with a bachelor’s degree, enrolled at DeVry University, a for-profit college, to get his MBA in 2009. Sidibe borrowed $ 84,503 to attend the school, but the program didn’t deliver on its promises to help him find a job, according to court documents. DeVry paid $ 100 million in 2016 to settle allegations from the Federal Trade Commission that the school lured students into attending and taking on loans with inflated job placement rates.

Donna Shaults, senior director, university relations for DeVry, wrote in an emailed statement that the school couldn’t discuss any individual student’s experience due to the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act. She added that the FTC case was resolved without an admission of liability or wrongdoing.

“We agreed to settle this case so we could channel resources more effectively toward our programs, services and investments that support our students,” she wrote.

The notice Sidibe received from the Department of Education warning he was at risk of losing his tax refund explained that “paying your debt by a mutually agreeable installment plan may make your loan(s) eligible for loan rehabilitation or payoff through consolidation, which will remove your loans from default status.” But borrowers don’t actually have to make payments in order to consolidate their debt out of default.

When Sidibe called the debt collector responsible for his student loans, but they didn’t say anything about Sidbe’s right to consolidate, the lawsuit alleges. Instead, the debt collector pushed him towards rehabilitating his loan, the lawsuit claims. Sidibe took them up on the offer and made his last rehabilitation payment on March 25, 2019. On April 1, the government seized his $ 2,698 tax refund, which included a child tax credit.

Sidibe, who works at a nonprofit and sometimes drives for Uber on the side, said he and his wife were planning on using the funds to take their two children to North Carolina to visit family friends — and repay those friends money they loaned to Sidibe’s family to help pay for necessities, like clothes for their children.

Eventually, Sidibe was able to connect with Tyler, who helped him get access to an affordable repayment plan. “It was for me, a big, big relief,” he said.

Sidibe decided to participate in the lawsuit as a way to try to get the refund money he lost back for his family.

A lost refund that could have provided relief during the pandemic

Though the coronavirus-era pause on student loan payments and collections was supposed to give borrowers financial breathing room during an unprecedented time, because of the challenges borrowers face getting out of default, it hasn’t always worked, the lawsuit claims.

Mary Perez, one of the plaintiffs, lost her $ 55,000 a year job as a restaurant manager at the start of the pandemic, and though she eventually was able to find work, she’s been part-time ever since. The $ 6,516 tax refund she expected to receive in the spring of 2020 would have helped her manage expenses, which she covers for her mother and two children.

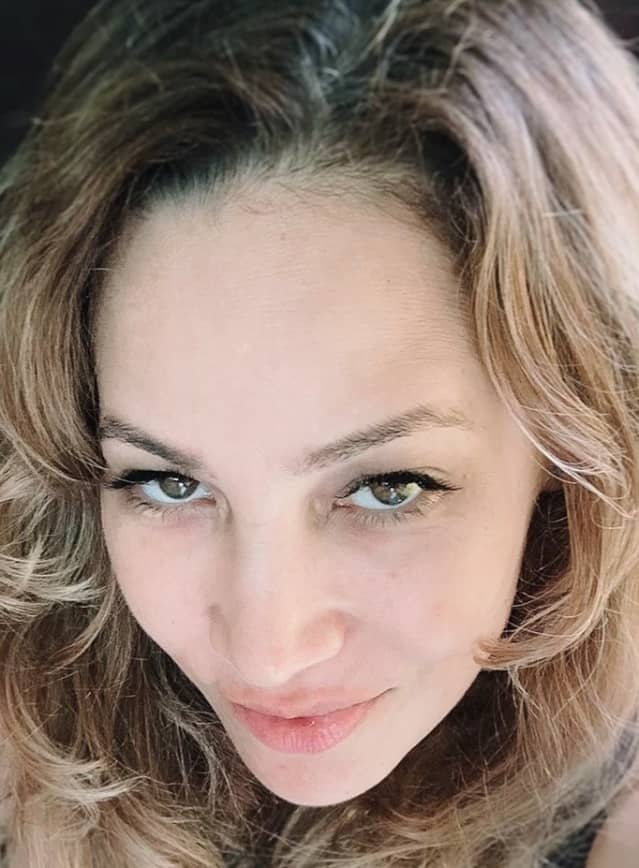

Mary Perez lost her tax refund due to a defaulted student loan.

Courtesy of Mary Perez

In 2019, Perez received mail from the Department of Education indicating that her tax refund could be at risk. Like in Sidibe’s case, the notice mentioned consolidation, but said Perez could become eligible by “paying your debt by a mutually agreeable installment plan.” That solution seemed impossible, given the precarious state of her finances. In addition, Perez had the right to consolidate without making payments first.

Perez also received a warning from a debt collector about the possibility she could lose her tax refund, according to the lawsuit, but the only option they offered for getting out of default was to make the nine rehabilitation payments, which would also be daunting given her financial situation.

The government seized her tax refund in February 2020. After losing her job, Perez struggled to afford necessities for her family. She turned to her children’s father for help and spoke about her predicament to friends, who referred her to a food bank.

“I never have done that, I have always been a person who provides and works,” Perez said in Spanish through a translator. She called a government-hired debt collector to see if there was anything they could do to help her, but because her refund was seized just before the pandemic, she didn’t qualify for the collections freeze that was part of the national emergency.

Tyler helped her become current on her loans through consolidation, but her part-time work still isn’t enough to keep her and her family afloat. “I need that money back,” she said through the translator. “I need it back so bad.”