As the Federal Reserve gears up to cull its bond holdings sooner and faster than it has previously, officials say a new tool, combined with lessons from the past, should help smooth the process and avoid the market upheaval its earlier effort ultimately triggered.

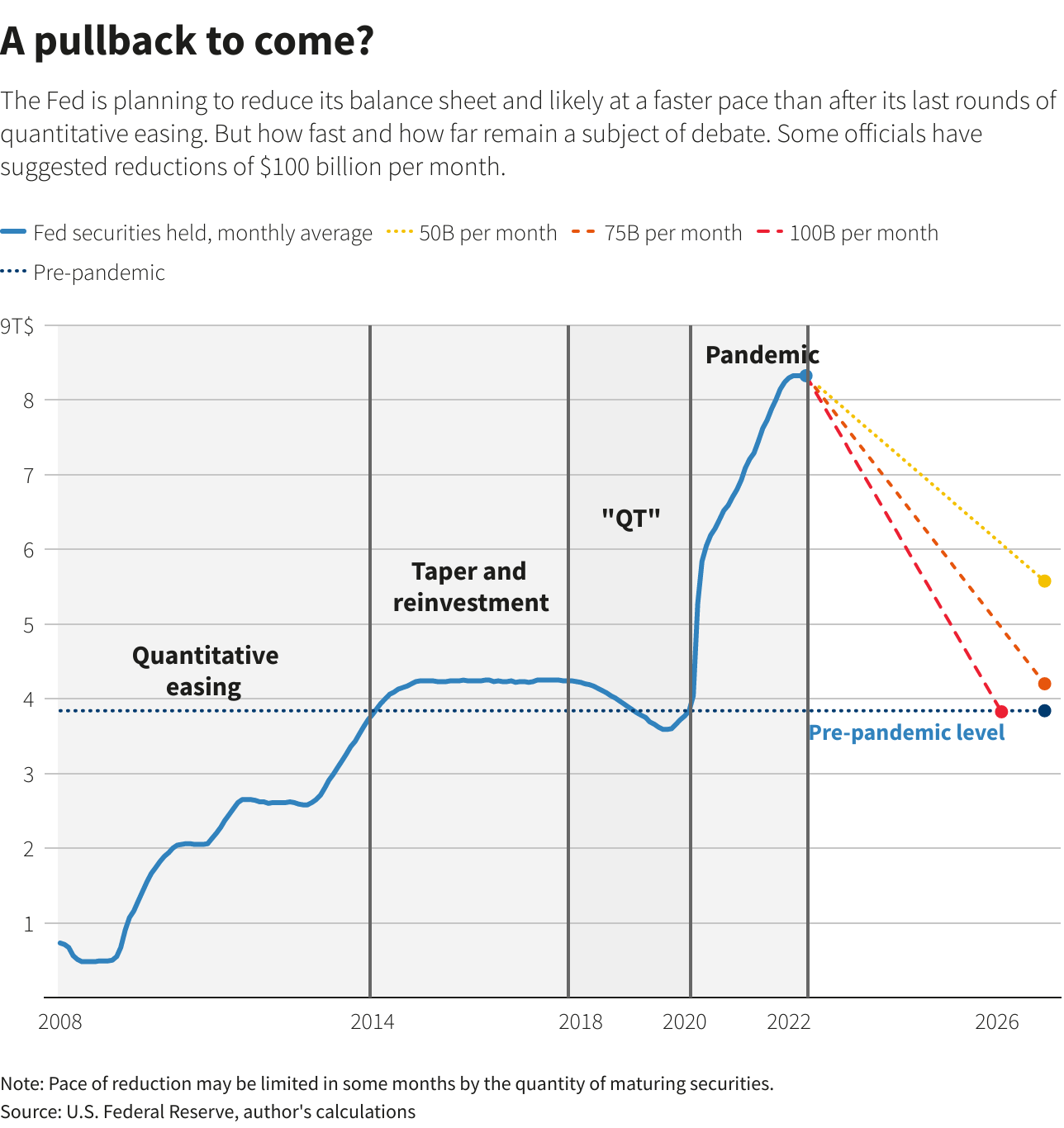

Still, Fed leaders will have to tread carefully as they figure out how much they can realistically shrink their roughly $ 9 trillion portfolio, and some analysts believe they will need to employ more aggressive measures than last time. It’s a critical question facing the Fed as it looks to right-size its asset holdings, which roughly doubled in less than two years as it amassed Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities to help lower borrowing costs and cushion the economy and markets from the coronavirus pandemic.

With unemployment back to near pre-pandemic levels and inflation running very high, officials say the same amount of support is no longer needed. But it is unclear how small the balance sheet will get. As officials feel their way down to a smaller balance sheet, they will need to keep a close eye on markets, and the economy, to know if they’ve gone too far.

WHAT COULD GO WRONG?

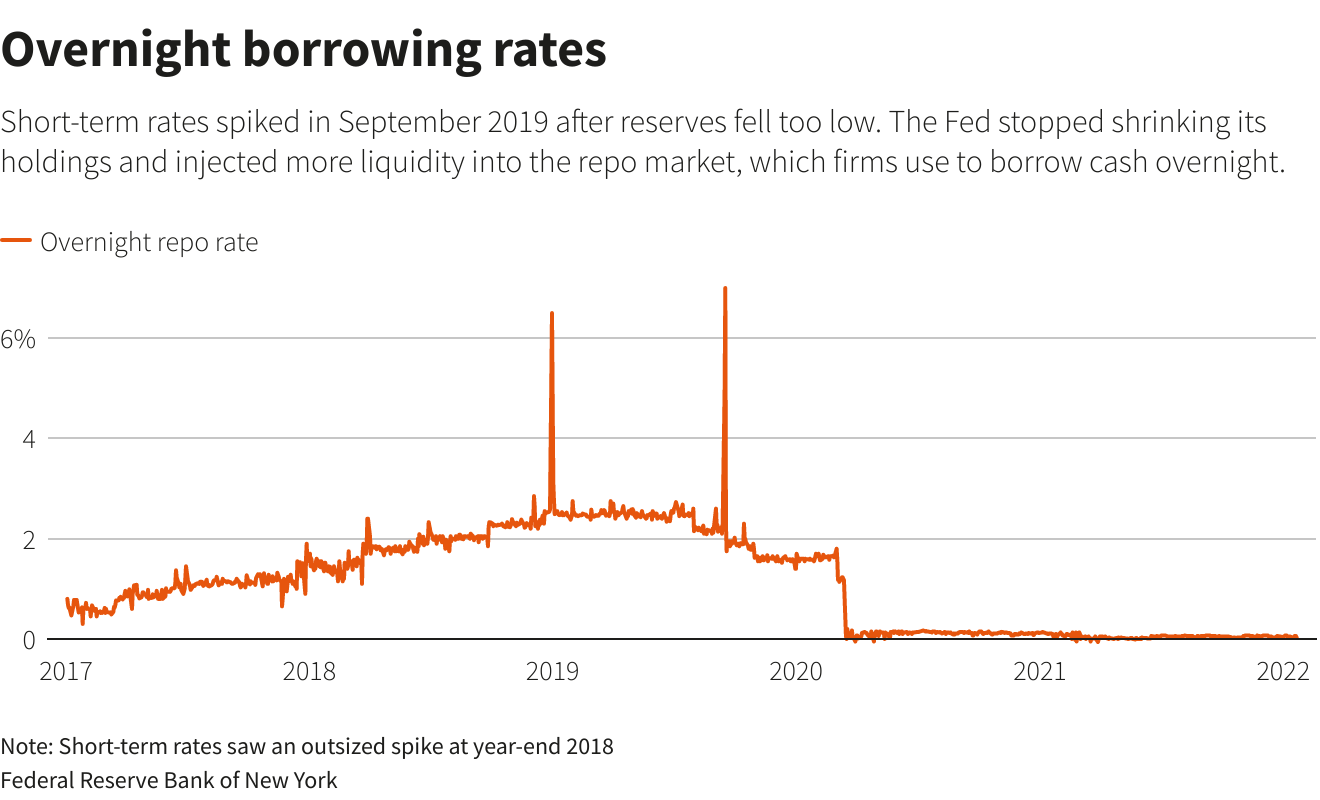

The last time officials tried to reduce their bond holdings, from the end of 2017 to autumn 2019, they only managed to shrink the balance sheet by about 15% or so before they ran into trouble. That was because the level of reserves, or deposits that banks hold with the Fed, got too low, which led to a spike in short-term borrowing costs in September 2019.

Officials are more ambitious this time, with some eyeing a level below where it was before the global health crisis began in early 2020 – a reduction of greater than 50%. But some economists say it’s not yet clear whether the Fed will be able to get that far, or if it can go even lower thanks to other central bank facilities now in place.

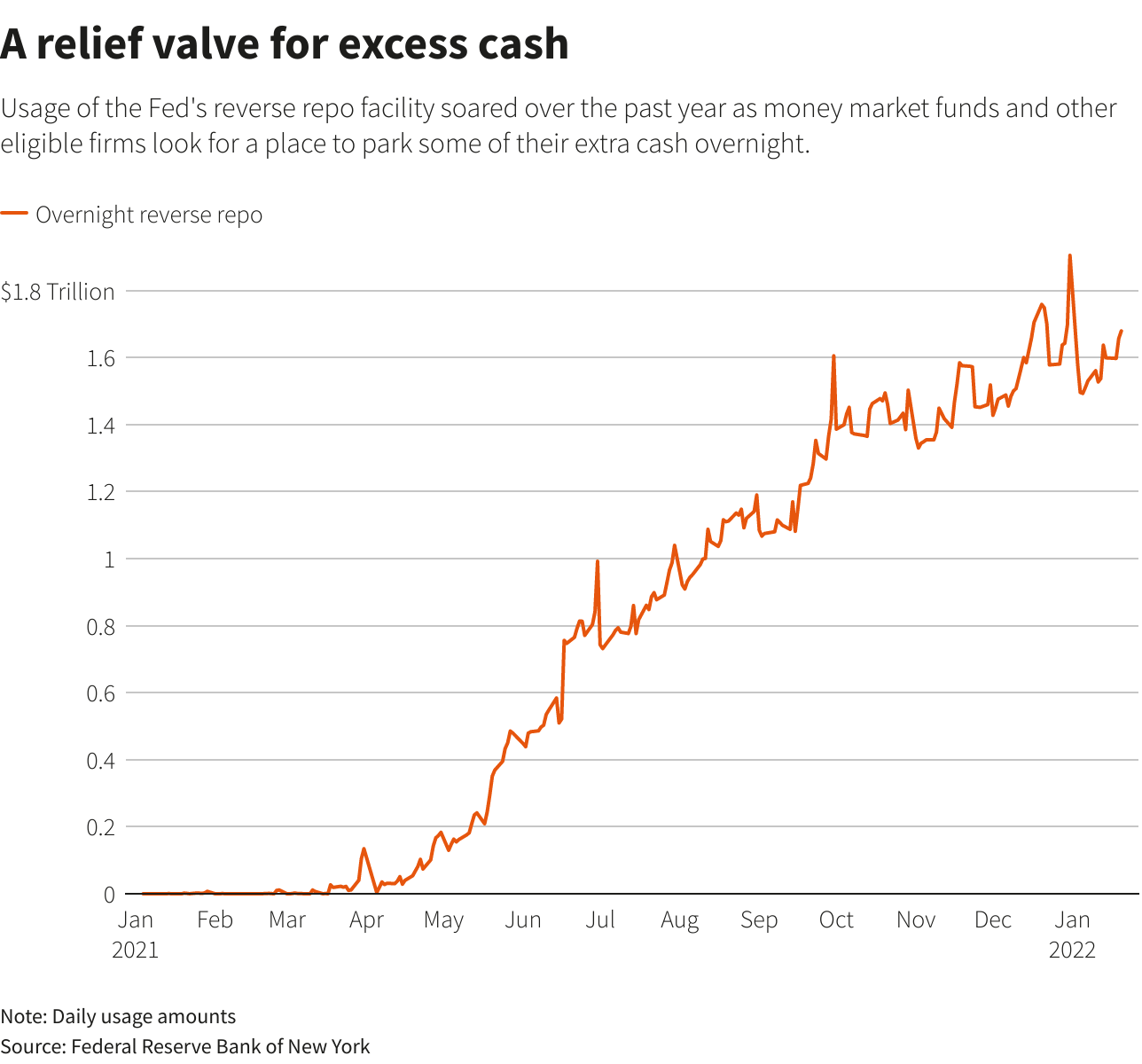

NEW TOOL COULD HELP A new tool set up last year, known as the standing repo facility, can serve as a backstop for banks in need of cash and may help to prevent another surge in short-term rates. Financial firms could instead borrow from the facility if they are running low on reserves. But analysts and economists say it will only work if banks feel they won’t be criticized for turning to the Fed for the temporary cash loans. Bill Nelson, chief economist at the Bank Policy Institute and a former Fed economist, compared the new program to the discount window, the long-standing emergency lending outlet many banks are reluctant to use because they don’t want to be viewed as being at risk. With the SRF in place, some firms should feel more comfortable holding Treasury securities with the understanding that “if they needed to, they could convert them to cash,” Nelson said. But that depends on the Fed making it clear that using the facility is a “normal course of business,” he said. EXTRA CASH ‘SLOSHING’ AROUND Over the past year, financial firms have been dealing with too much cash – a trend that is evident in the high popularity of another Fed tool that lets firms park cash with the central bank overnight. Usage of the program, known as the reverse repo facility, has averaged $ 1.5 trillion a night over the past three months. That suggests the Fed can probably afford to reduce its balance sheet by at least that much before it starts to encounter scarcity issues, says Tiffany Wilding, a PIMCO economist and a former analyst at the New York Fed. “There’s more money sloshing around in the system now than banks want,” Wilding said. But usage of the reverse repo program may not go straight down as the Fed shrinks its holdings, said Nelson, so officials will need to move carefully.

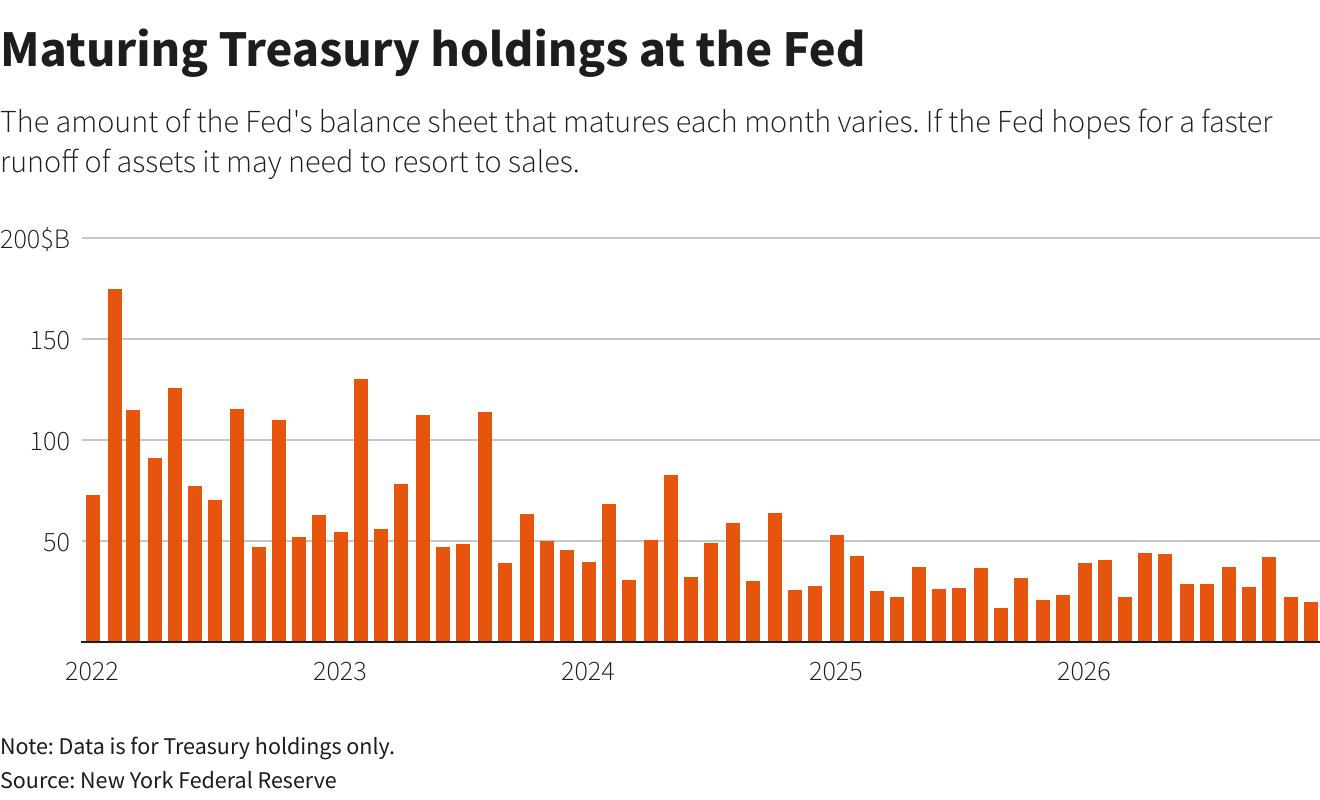

WILL THE FED HAVE TO SELL BONDS OUTRIGHT?

That’s a big unknown, and while Fed officials have not ruled anything out, they’ve generally shied from discussion of actively selling assets rather than allowing the reduction to occur passively by letting bonds roll off the portfolio as they mature. It’s not clear that the portfolio’s maturity schedule will allow the Fed to shrink its holdings as fast as some would like, however.

Some analysts, like Zoltan Pozsar at Credit Suisse, argue that the Fed may be pressed into bond sales this time because of the size of the inflation threat, the run-up in risky assets during the Fed’s quantitative easing phase and a flattening Treasury yield curve.

This time, “outright asset sales, if inflation, exuberance, or a curve inversion so dictate, are not at all unlikely,” Pozsar wrote in a report.

HOW WILL THEY KNOW THEY’VE GONE TOO LOW?

The balance sheet levels seen before the pandemic may not be a good gauge for how low holdings can get this time around. One factor is that “banks’ demand for reserves varies over time,” Lorie Logan, an executive vice president in the Markets Group of the New York Fed, said earlier this month during an interview with the Macro Musings podcast.

To figure out if reserves are falling too low, the Fed will keep an eye on money markets, Logan said. As she and other New York Fed officials explained in a recent blog post, the relationship between the effective federal funds rate (EFFR), or the Fed’s main target rate, and the interest rate that the Fed pays on reserve balances (IORB) is important.

The two rates trade further apart when reserves are abundant, as they were between 2013 and 2014. And the rates trade closer together when reserve balances are declining, as they were between 2017 and 2019.