With consumer prices rising at the fastest pace in nearly 40 years, the Federal Reserve is signaling that it will soon begin raising interest rates. But the most important question hasn’t even been asked: Would higher rates do anything to quell inflation?

Breaking news: Consumer prices rise 0.5% in December and push U.S. inflation rate to nearly 40-year high of 7%

It may be heresy to those who think the Fed is all-powerful, but the honest answer is that raising interest rates wouldn’t put out the fire. Short of throwing millions of people out of work in a recession, higher rates wouldn’t bring supply and demand back into balance, a necessary condition for price stability.

The Fed (and those who are clamoring for the Fed to raise rates immediately) have misdiagnosed the problem with the economy and are demanding the wrong kind of medicine.

The problem isn’t too much demand; it’s too little supply.

Breaking news: Powell paints the picture of a soft landing, says Fed can cool inflation without damaging labor market

Not much borrowing

The justification for a rate hike now seems to be that cheap credit has allowed spending to overrun the economy’s ability to produce what people want to buy. With credit-fueled demand exceeding supply, prices are rising quickly. By raising short-term rates, the Fed hopes to slow the economy by making it more expensive for consumers and businesses to borrow money.

But does that story hold water right now? No.

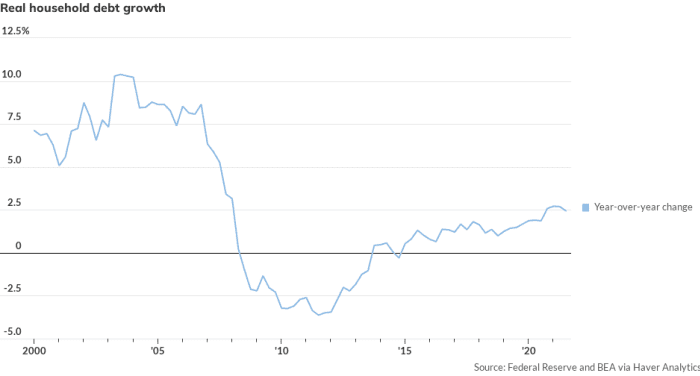

Household debt is growing slowly despite very low interest rates.

MarketWatch

In the past year, as inflation has ignited, credit growth has been anemic despite very low interest rates TMUBMUSD10Y, 1.792%. Real household debt has increased just 2.2% annualized since the pandemic began while business borrowing is growing at the slowest pace in eight years, even after businesses loaded up on cheap pandemic loans early in 2020.

Raising rates would have little impact on the economy because credit growth is already weak.

it doesn’t look as if easy credit is the problem. But something is causing prices to rise—what could it be? Interest rates have been extremely low since 2009, but something has changed recently. I wonder what it could be? Perhaps a global pandemic had something to do with it.

Tepid overheating

Larry Summers and other economists who want the Fed to hike insist that the economy is overheating. But what a strange kind of overheating it is! Through the third quarter, the economy had grown at just a 0.8% annual pace since the pandemic began two years ago and key sectors show considerable slack, which means the economy could run a lot hotter if the obstacles to growth were cleared away.

The labor market is down 3.6 million jobs from pre-pandemic levels. The labor-force participation rate is down 1.5 percentage points, and not all of the people who’ve dropped out are willing retirees. More than 12 million people are either looking for work, or would like to work if they could. The capacity utilization rate for U.S. industry is at 76.8%, down from the recent peak of 79.9% in 2018.

These figures don’t indicate that output is too high.

Incomes and spending

Incomes aren’t overheating, either.

Real disposable personal incomes soared during the pandemic from stimulus checks, tax and debt relief, and unemployment payments, but per-capita real incomes are now running at a level just 1.9% higher than when the pandemic began.

Consumers may have a lot of savings tucked aside, but their incomes aren’t growing very fast right now. Remember, most of the savings are at the top of the income scale, not at the bottom where people are struggling with not only rising prices, but with hazardous working conditions and spotty arrangements for making sure their children and elderly relatives are well cared for.

Aggregate spending isn’t out of control (it’s up 2.4% annualized since the pandemic began), but the pandemic has steered spending to some industries and away from others. Durable goods are in heavy demand (up 11% annualized), but demand for services such as going to the movies (down 14%) or for foreign travel (down 52%) has dried up.

Opinion: Inflation is running rampant in the U.S.—here’s where it is, and isn’t

Stopping inflation means controlling the pandemic and helping the economy adjust to a new normal. To strengthen and shorten our supply chains for the inevitable next wave or next pandemic, we need significant investments in new domestic and global supply capacity, including manufacturing and transportation. Above all, it means luring back millions of potential workers who are put off by lousy, unsafe and low-paying jobs.

Higher interest rates won’t help us make those adjustments.

Wages falling behind

In fact, while higher wages would help lure back workers, the Fed is fixated on its fear of the dreaded wage-push inflationary spiral, in which workers who’ve gotten a taste of higher wages will insist on getting more every year, forcing their bosses to knuckle under to their demands and leaving them with no option but to raise their own selling prices so they can make the payroll.

No one who’s ever worked for wages or paid them could ever believe such a ridiculous story. Businesses raise their prices when they can get away with it. Full stop. Workers may have once had some bargaining power over wages, but their clout has eroded. Even with strong gains this year, weekly wages have lost about 2% of their purchasing power to inflation over the past year.

The Fed shows no such concerns about the inflationary threat posed by higher profits for businesses or higher asset prices for investors. Why? Because higher profits and stock prices are thought to encourage more investment.

But that’s another theory that has no basis in reality. The level of interest rates has almost no effect on investment decisions by businesses, who look at the profit potential first and foremost. The evidence is overwhelming that ultralow interest rates for the past decade did nothing to encourage private investment.

Prices are going up because crucial inputs—labor, electronics, energy, housing, transportation—are in short supply. Normally, the way to solve this imbalance would be to give workers and businesses incentives to increase their supply. That’s the beauty of market economies: Prices provide continual signals about the balance of supply and demand for particular goods and services. Higher prices tell buyers to buy less and they tell producers to produce more until supply and demand are in balance.

Markets often cannot reach this equilibrium on their own, so policy makers must push and pull their levers to keep the macroeconomy on the right track.

Wrong for the job

The Fed has been assigned the job of fixing this. Unfortunately, the Fed doesn’t have the tools to do it. Monetary policy works (in theory) by tweaking demand, but it has no direct impact on supply.

Furthermore, it’s become apparent over the past few decades that the Fed “has much less control over spending (and therefore inflation) than is widely taken to be the case,” as heterodox economists Dimitri B. Papadimitriou and L. Randall Wray of the Levy Institute of Bard College put it in a recent policy paper, “Still Flying Blind After All These Years.”

Papadimitriou and Wray argue that the Fed gets a lot more credit for the Great Moderation of the macroeconomy over the past 40 years than it deserves. The Fed, they say, wandered fruitlessly in the wilderness for 40 years searching for a workable theory of inflation, finally settling on the spurious idea that inflation is caused by “inflation expectations.” According to this idea, managing inflation is a simple matter of managing expectations (as measured by bond yields and surveys): If people (consumers, business leaders, workers, and investors) don’t expect higher prices, then prices won’t rise.

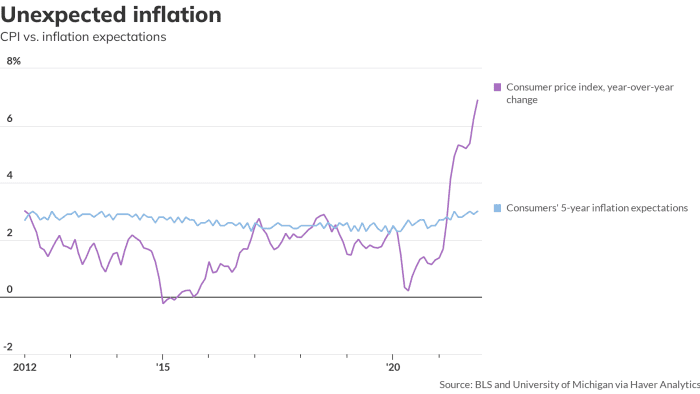

Surveys of expected inflation didn’t predict the actual inflation that was unleashed this year.

MarketWatch

The theory is incoherent, unprovable and probably gets the causation backward, Papadimitriou and Wray say. Expectations don’t drive inflation, it’s the other way around. The strongest evidence for that conclusion is that the current bout of inflation was not preceded by an increase in expectations. But once inflation started rising, so did expectations.

And yet the Fed still clings to this theory. The only justification for raising interest rates now (since rate hikes cannot restore price stability by boosting the supply we need) is that failing to act decisively against inflation now would “unanchor” inflation expectations. The tail is truly waging the dog.

Maybe it’s time to rethink how we try to manage the economy by giving more of the responsibility for controlling inflation to fiscal and regulatory policy makers, who can at least design their policies to aim at the target.

Rex Nutting is a columnist for MarketWatch who’s been writing about economics and the Fed for 25 years.