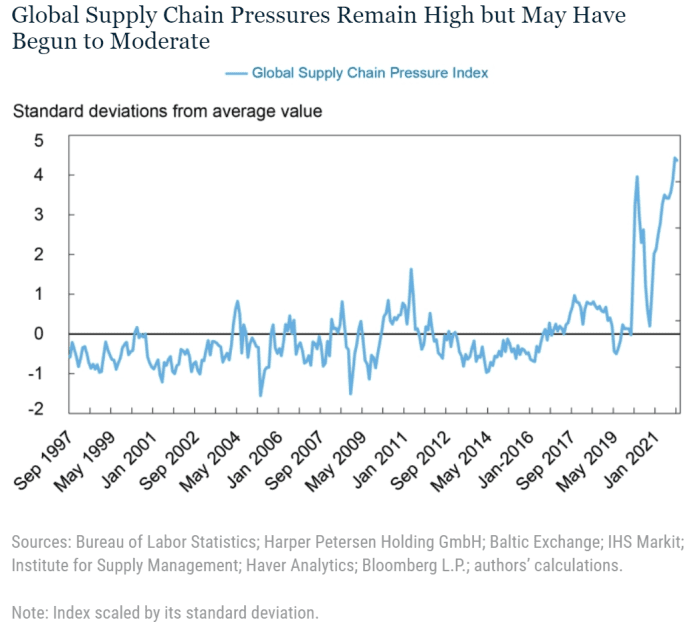

The global supply chain is still a mess, but pressures may have peaked, according to an index put together by researchers at the New York Federal Reserve.

The Global Supply Chain Pressure Index, or GSCPI, surged in the early days of the pandemic as China imposed lockdown measures, then fell briefly as world production began to rebound in the summer of 2020. The gauge jumped sharply as winter 2020 approached and COVID-19 cases were resurgent.

More recently, the index “seems to suggest that global supply chain pressures, while still historically high, have peaked and might start to moderate somewhat going forward,” wrote New York Fed economists Gianluca Benigno, Julian di Giovanni, Jan J. J. Groen, and Adam I. Noble in a Tuesday blog post.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Massive supply-chain backups, including clogged ports, have been blamed on surging consumer demand for goods as the global economy continues to recover from the initial near-shutdown sparked by the pandemic in the spring of 2020. The supply-chain woes have been blamed for shortages of computer chips and other components that have crimped production of autos and other goods, while also contributing to inflation pressures.

The researchers said they devised the gauge, which integrates more than two dozen commonly used metrics, in an effort to provide a more comprehensive summary of disruptions affecting global supply chains.

The metrics include measures of cross-border shipping costs: the Baltic Dry Index, which tracks the cost of shipping raw materials, such as coal or steel; and the Harpex index, which trackers container shipping rate changes in the charter market for eight classes of all-container ships. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics puts together price indexes that measure air-transportation costs for freight to and from the U.S. The index also uses outbound and inbound airfreight prices for transport to and from Asia and Europe.

A second set of indicators used to put together the gauge are based on country-level manufacturing data from purchasing manager index surveys. For the U.S., where PMI data only goes back to 2007, the readings are combined with the Institute for Supply Management’s manufacturing survey.

As the chart shows, the GSCPI has spiked around past economic shocks, but those rises have paled in comparison to the jump sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic, which all but shut down the global economy in the spring of 2020.

The researchers said a future post would quantify the impact of shocks to the GSCPI on producer and consumer price inflation.