I have long been a fan of working longer. Claiming Social Security at age 70 rather than age 62 produces monthly benefits at least 76% higher. These benefits not only last a lifetime but are also adjusted for inflation. Most people who work to age 70 will be able to maintain their preretirement standard of living.

Until recently, the trend of rising disability-free life expectancy in the United States suggested increasing scope for longer working lives. Recent developments, however, may have stalled this progress. Both self-reported and objective measures of health have worsened over the past two decades. This decline has been particularly acute for workers without a college degree. At the same time, the separate trend of rising educational attainment, which helped spur past improvements in disability-free life expectancy, has largely played out.

To reassess how long people may be able to work, my colleagues have just completed a study that examines “working life expectancy” for all individuals and by race and education.

The calculation of “working life expectancy” requires data on: 1) the probability of dying; 2) the probability of being institutionalized; and 3) the probability of having work-limiting disabilities in the non-institutionalized population.

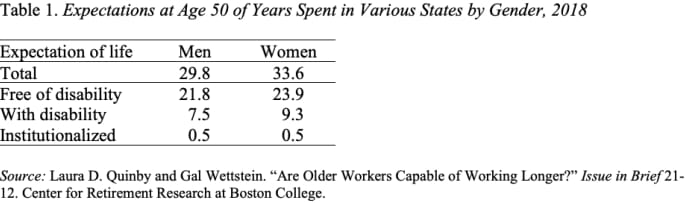

Combining these probabilities suggests that a 50-year-old man could expect to live an additional 29.8 years, and in 21.8 of those years he would be capable of work. For a woman, the corresponding numbers are 33.6 and 23.9. On their face, these results might seem encouraging — the average person can work until their early 70s.

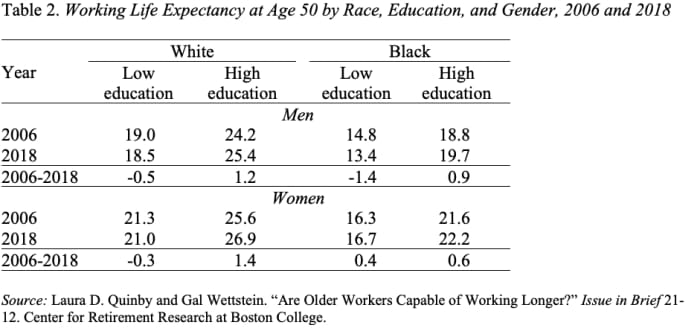

However, the average does not tell the full story. A stark divide exists by education: both high-education Black and white individuals experienced an increase of roughly one year of working life expectancy from 2006 to 2018. In contrast, most low-education groups actually saw a decline, with the exception of Black women.

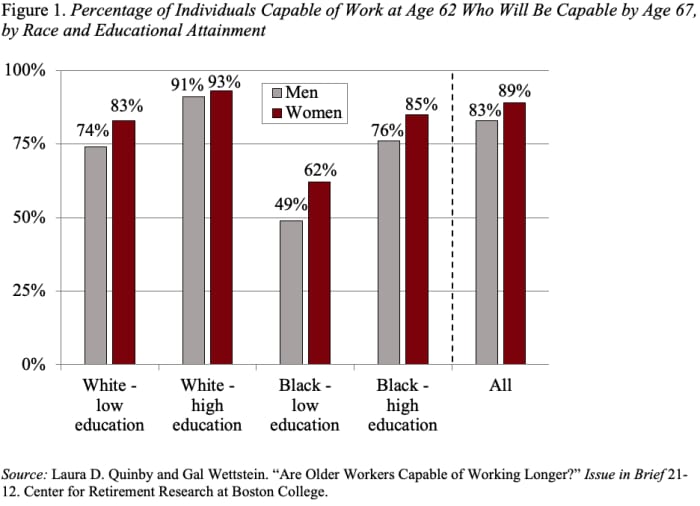

The key question is how long individuals in each group can be expected to work. To answer that question, the researchers took individuals who are expected to be working at 62 and calculated the probability that they will still be capable of work at Social Security’s Full Retirement Age of 67 (see Figure 1).

The exercise shows two things.

First, roughly 85% of those working at 62 can work to 67, which means that the prescription to work longer is still useful advice for much of the population.

Second, a substantial portion of Black workers and individuals with low education will not be able to work to 67 and would be severely hurt by any increase in the FRA.