When reports of a new coronavirus first started circulating in early 2020, city officials in Napa, California, knew they were in trouble.

Napa is about 50 miles north of San Francisco, in the heart of California wine country. Tourism-related revenues account for roughly one-quarter of the city’s budget, Finance Director Bret Prebula said, and another 19% comes from sales taxes, most of which are collected from restaurants.

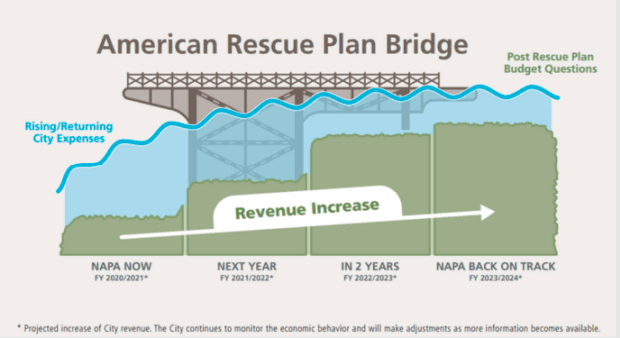

Last March, with about three months left in fiscal 2020, Napa cut $ 10 million, or roughly 10%, from its budget. Fiscal 2021 was even leaner. Now, Prebula forecasts tourism revenues won’t be back to pre-pandemic levels until 2024 — even as expenses just keep rising.

“Even if we get a good recovery, our expenses are going to outpace revenues,” Prebula told MarketWatch. “The pandemic has only accelerated the issue. We’ve cut the fat as much as we can and we are getting toward core employee and service delivery. But we need to operate the city at the expectation of the community.”

Across the country, those watching the public finance sector have let out a collective sigh of relief. Nightmare scenarios imagined last year in the midst of the crisis mostly haven’t come true. But countless communities still face their own versions of what Napa is seeing.

From downturn to crisis

Many cities only recently were able to shake off the lingering effects of the Great Recession when COVID-19 erupted. Most also face an uneasy balancing act as legacy costs, including pensions and healthcare, swell to crowd out day-to-day budget needs. And while federal stimulus dollars will be a huge help, in many cases it won’t be enough.

Napa expects to receive nearly $ 15 million from the American Rescue Plan, which was passed March 12, and will be used to plug revenue holes for fiscal years 2021, 2022, and 2023.

“When I say it’s a lifeline, I’m not joking,” Prebula said.

Restaurants and tasting rooms across wine country are more fully reopening as vaccination rates ramp up, but swaths of California also face “historic” drought conditions and potentially another extreme wildfire season.

Read: California’s fabled wine region is having ‘the most horrible, devastating and catastrophic year’

Even with Napa’s injection of federal pandemic aid, it still leaves big costs for the city, including infrastructure expenses deferred from as far back as the Great Recession, which Prebula reckons will eat up another $ 5 million to $ 7 million a year. He doesn’t know where that money will come from.

Emily Swenson Brock is with the Government Finance Officers Association, which represents 21,000 people like Bret Prebula from cities and towns around the country. Not only is there no data to quantify the pandemic’s hit to budgets, but the impacts to both revenues and expenses have been so uneven, it’s hard for Brock to even make generalizations about what she sees.

Communities dependent on travel and tourism lost big in terms of revenue, Brock said in an interview, pointing to challenges stretching from Nashville to New England towns, as well as smaller cities in the heartland.

In general, counties bore more of the health costs of the pandemic than did local communities, and are now shouldering the costs of the vaccine rollout. In contrast, Brock said, “Cities are the ones who deal with home and food insecurity, and other social service needs, which have exploded.”

Related: In one chart, how U.S. state and local revenues got thumped by the pandemic — and recovered

A map for city aid

Many city officials Brock speaks with plan to use their American Rescue Plan money for revenue replacement, like Napa, but some are also thinking creatively about deploying it for big-ticket costs like infrastructure, or for something that might be a revenue generator in the future.

An interactive tool that estimates how much each municipality will receive, tabulated by the National League of Cities, can be found here. To receive money directly, a community must have at least 50,000 residents; for places with smaller populations, Congress has allocated money to states with the expectation it will “flow down,” in Brock’s words. She and others are watching that process carefully, since smaller communities are inherently more vulnerable to economic downturns to begin with, and states don’t have the best track record of sharing funds with their localities.

It’s also important to note that earlier rounds of federal pandemic aid, like enhanced unemployment, the Paycheck Protection Program, and so on, helped local economies, even if they weren’t direct transfers.

“They helped hold the line,” said Natalie Cohen, a longtime public finance analyst now running a consulting firm called National Municipal Research. As a result, “This is a whole different animal than the Great Recession,” she said.

The legacy of the last downturn is felt keenly in the public finance sector, and it’s clear that Washington got the message. If the federal government had allocated as little to states and locals during this recession as in 2009, Prebula said, “we’d be in a great depression now.”

As he manages Napa’s budget now, he’s keeping in mind the lessons of a decade ago. “Decisions were made to focus on the day-to-day service issues instead of infrastructure, but we never caught up and those issues hit us smack in the face,” Prebula said.

“What we’re trying to focus on is those core areas you need to fund and find revenue to address them. That’s a holdover from the Great Recession,” he said. “We are trying to not be a negative legacy. They linger with you as an albatross around the neck.”

Read next: Chuck Reed warned of city services ‘insolvency’ after the Great Recession. He thinks the corona-crisis may be worse.