There are 3 million older Americans—defined as age 55 and older—who are now out of the U.S. labor force because of the pandemic and recession.

That’s according to a study by the Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis (SCEPA) at The New School of New York.

The data shows a roller coaster-like pattern, beginning with a sharp drop in employment last Spring, followed by a recovery between May and August, and a further drop through January of this year.

Foe context, there were 37 million older workers in the labor force this time a year ago, says SCEPA’s Michael Papadopoulos.

“The recovery has slid backward for older workers,” he says, nothing that the labor-force participation rate (the percentage of the workforce that has a job or is looking for one) among this age group “has dropped continuously since August and is now at its lowest point since the recession began.”

This rate hasn’t just fallen. When compared with midcareer workers— (ages 35-54)—it has fallen five times faster. Since the downturn resumed in August, for example, the participation rate for the middle-aged group has declined 0.5 percentage points, but for older workers, it has fallen 2.7 points.

These aren’t just data points, of course. They reflect deep economic pain and anxiety for millions of older Americans, many of whom may never work again—at least not at the same salary and with the same benefits they enjoyed before the downturn.

“Of the 3 million older Americans who are now out of the labor force, about a third of them could fall below the poverty line,” Papadopoulos estimates. And keep in mind SCEPA says the real poverty line is actually about twice the federal estimate. The federal government thinks that a single person’s poverty level is about $ 12,800 a year, and $ 17,420 for a couple. SCEPA says such figures are absurdly low, given things like high housing costs and taxes in certain parts of the country, along with items that hit seniors disproportionately, like the surging cost of prescription drugs.

Read: What will low interest rates do to retirement savings?

“We think the true poverty level is about $ 24,000 for an individual and $ 30,000 for a couple,” Papadopoulos says, adding that the “downward mobility” that many older Americans are now experiencing will feed into future poverty rates.

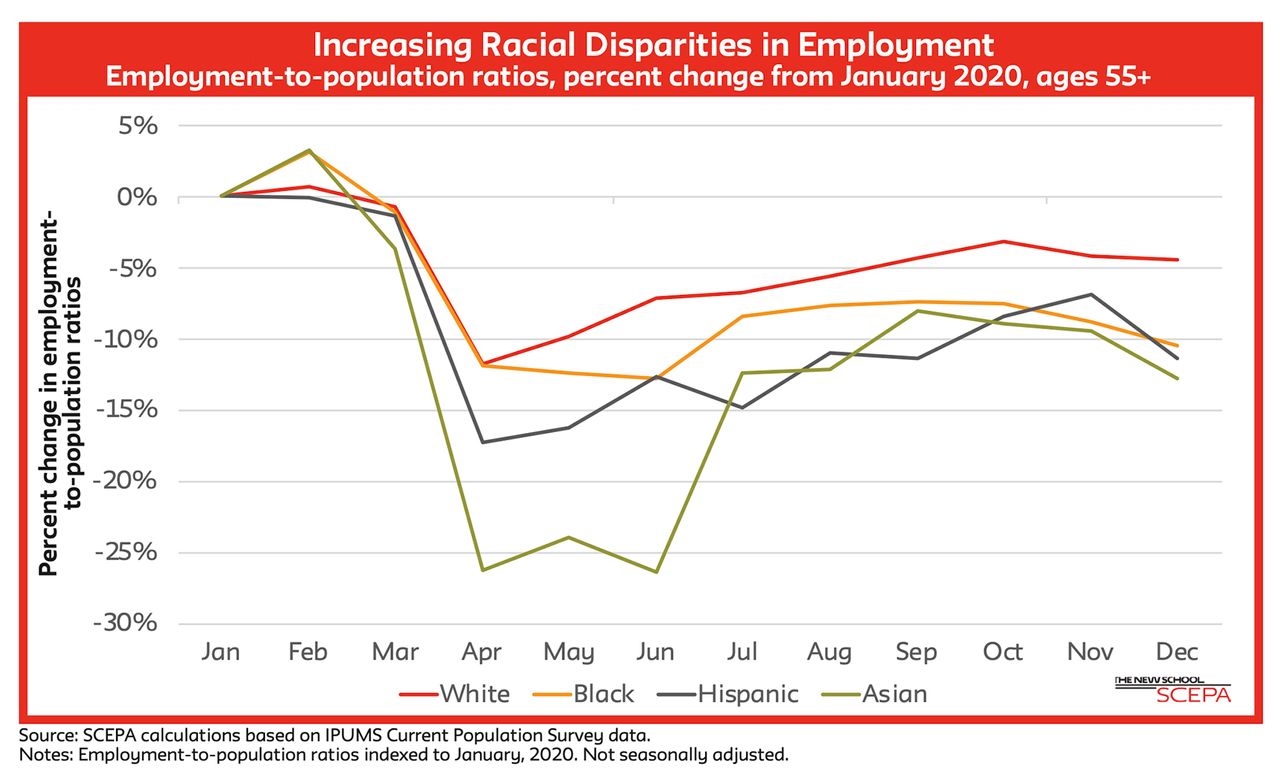

The SCEPA report also reinforces a longstanding fact, namely that nonwhite workers fare worse during a downturn. “The decline in employment for Black, Hispanic, and Asian older workers was more than twice that of white older workers,” it says.

“Older workers have a deeper hole to dig out of,” says Papadopoulos, and “nonwhite older workers not only face that, but the double disadvantage of racial discrimination as well.”

“I’m sorry this news is bad,” SCEPA’s director Teresa Ghilarducci tells me. “But it’s based on numbers that are precise and calculated. I feel this is quite startling.”

Ghilarducci says the hope she had that things were getting better for older workers over the summer has faded. Because it’s generally harder for older workers to find jobs—age discrimination is alive and well—those who are unable to find decent work will have to begin drawing down retirement assets early, and, if they’re 62, begin taking Social Security.

Read: Turned 60 last year? Social Security has an unpleasant surprise for you

The problem with the former is that older workers who want to work for a few more years—or need to work—will have to tap into an IRA or 401 (k) instead of contributing to them, perhaps getting a company match and letting those assets grow.

The problem with the latter—taking Social Security at 62, the earliest possible age—is that it means reduced benefits. According to the Social Security Administration, the average benefit in 2021 is $ 1,543 a month.

For many older Americans whose fortunes have fallen in the last year—through no fault of their own—and experienced this “downward mobility,” Ghilarducci offers this grim prognosis:

“It’s really the end of the line for them,” she says.